Kangaroos in the Hauraki Gulf

the remarkable story of Kawau Island’s wallabies

Auckland Council is currently spending millions of dollars to eradicate wallabies from Kawau using 1080, guns, dogs and drones. It’s a divisive issue unfortunately and I frankly am not a supporter. But love them or hate them, islanders may be interested to know a little about the backstory of these misplaced members of the kangaroo family before they are gone forever.

As well known, their story begins in 1870 with Sir George Grey, twice governor and later premier of New Zealand.

During his second term as governor in 1862, Grey purchased Kawau Island and built the mansion which still stands at the head of the Governor’s Bay on Bon Accord Harbour.

The elegant Grey chose to stock his island with exotic creatures, many from the colonies he had governed; ostriches, zebras, antelopes and monkeys from South Africa; kookaburras, parrots, emus and kangaroos from Australia and an arboretum of rare and tropical trees and plants from all over the world.

Most of this exotic menagerie, eventually died-out but the Australian introductions, kookaburras, eastern rosellas, brushtail possums and at least five species of wallabies survived – the latter despite the attentions of large shooting parties during Grey’s lifetime and after.

One species of wallaby, the large Black-striped Wallaby (Notamacropus dorsalis) probably became extinct on the island by the middle of the 20th century; and the Brushtailed Rock Wallaby (Petrogale penicillata) is claimed to have been eradicated from Kawau about 15 years ago.

If that is the case there are now three wallaby species surviving on Kawau, the Tammar (Dama) Wallaby (Notamacropus eugenii), the Parma Wallaby (Notamacropus parma) and the Swamp Wallaby (Wallabia bicolor).

Tammar Wallaby

Known to locals, as the ‘dama’, and the ‘silver grey’, (Tammar is its Australian common name), also known as the Kangaroo Island wallaby. The Tammar Wallaby was likely the first kangaroo species ever to be seen by a European. In 1629 the Dutch navigator, Francusco Pelsaert, reported it on the Abrohol Islands off Western Australia. Its predominant silvery colouring is contrasted with reddish coloured shoulders. The tail is long and thin. It grows up to half a metre in height.

Tammar (Dama) Wallaby (Notamacropus eugenii) [photo Jean-Paul Fererro]

On Kawau it grazes on open grassy areas (60% of its diet) but also in regenerating native forest and pine plantations where it browses certain native understory plants, especially hangehange and karamu while ignoring others such as rangiora. mingimingi and kawakawa.

In Australia the Tammar is noted for its remarkable ability to drink sea-water – quite a useful attribute for an island dweller in a climate like Australia. As an islander by ancestry one imagines that Kawau would not have been a particularly difficult place for it to adapt to.

Apart from Kawau Island the Tammar is also found in the Rotorua area. [1]

Parma Wallaby

The Parma also known to locals as the ‘white-throated’. This is the smallest wallaby species on Kawau and the smallest species in the genus Macropus. Its coat is brown with a distinctive white chin and throat and white tip on its tail, it has a thin dark stripe visible on the back of the head from ears to shoulder. It’s mainly nocturnal. While each species of wallaby on Kawau has an interesting and distinctive natural history and ecological niche undoubtedly the most fascinating backstory is that of the parma.

Parma Wallaby (Notamacropus parma) [photo Jean-Paul Fererro]

The Parma Wallaby was first discovered for science in 1843 by the British collector John Gould in the IIlawara and Cambewarra districts of coastal New South Wales. Gould commissioned one John Gilbert to collect “as many specimens and crania as convenient” unfortunately for Gilbert he was unable to complete his commission due to his being speared to death by local aborigines in 1845.

Never common, by 1888 the Parma was considered rare. With European settlement, its preferred habitat, wet eucalyptus forest was substantially reduced for farming. Natural predators like the dingo and carpet snake were joined by newcomers such as the European red fox which had a particularly devastating impact on local populations. (In 1988 management at Melbourne Zoo was extremely embarrassed when red foxes broke into the wallaby enclosure killing a number of Parmas, all of which were descended from Kawau.)

Consequently sightings in Australia became increasingly rare. There was a confirmed sighting in 1921 and again in 1932 but by 1942 it was believed to have followed the beautiful Toolache Wallaby into extinction.

In 1957 Dr W. Ride of the CSIRO in Canberra reported the species “apparently extinct” after the only trace he could find of it was 12 specimens stored in various world museums. It was during this research that Ride hit upon the idea that skins in the Australian Museum from Kawau Island which were believed to those of the Black-striped Wallaby were possibly mis-identified Parmas.

At Ride’s request, the New Zealand DSIR from 1961 to 1966 mounted four expeditions to Kawau. As well as looking for signs of the Parma, the DSIR, was interested to know whether the Black-striped Wallaby (last sighted in 1931) had survived.

The DSIR expedition was led by the Polish emigré Dr Kazimierz Wodsicki and Dr J.E.C (John) Flux. In 1965 the DSIR explorers met with success when two wallabies fitting the description of the Parma were collected. This was confirmed the next year when five more Parmas were collected and sent to Canberra for identification.

Wodzicki and Flux announced their findings in the Australian journal of Science (1967). The rediscovery of this extinct species caused a sensation amongst Australian scientists. Amidst celebrations plans were immediately drawn up to bring the long-lost wallabies home.

Heeding Wodzicki’s only half-humorous warning “that this species must not be allowed to become extinct again”, the international Union for Conservation of Nature sought and gained full protection status for the Parma wallaby from the New Zealand government. In December 1967, 31 Kawau Parmas were flown to Melbourne and distributed to Melbourne Zoo, Healesville Wildlife Sanctuary and Monash University. From 1967 to 1975 736 Kawau Parmas were live-captured and exported to zoos and wildlife parks in Australia and around the world.

Then…at the height of the trans-Tasman repatriation, a reptile park owner in Gosford, New South Wales, reported he’d come into the possession of female Parma wallaby. In 1972 a field survey carried out by G.M. Maynes rediscovered a population of Parmas in the Moonpar State Forest on the Dorrigo plateau inland from the Coffs Harbour.

Further expeditions went on to establish that Parmas were present in other parts of New South Wales and though rare were not endangered.

This in meant that the celebrity Kawau Parmas, lost their precious status and removed from the Red Data Book. In 1984 the New Zealand government revoked their protected status, returning them to their lowly pest status – with lethal consequences. So literally from hero to very soon zero.

But interestingly in Australia all the Parma Wallabies held in zoo’s and wildlife parks are descended from Kawau Island ancestors.

The two separate populations living in Australia have presented scientists with an opportunity to study what effect one hundred years of complete separation in two quite different environments has had on the species. One important discovery was that the female Kawau parma and their descendants are significantly smaller that the indigenous parma females (Maynes 1977). Scientists conclude that the smaller size of Kawau wallabies has become “genetically fixed” and further suggests that this could be an example of ‘dwarfism’ – an evolutionary phenomenon in which mammal populations on islands evolve to a smaller size than their conspecifics living on mainlands.

Swamp Wallaby

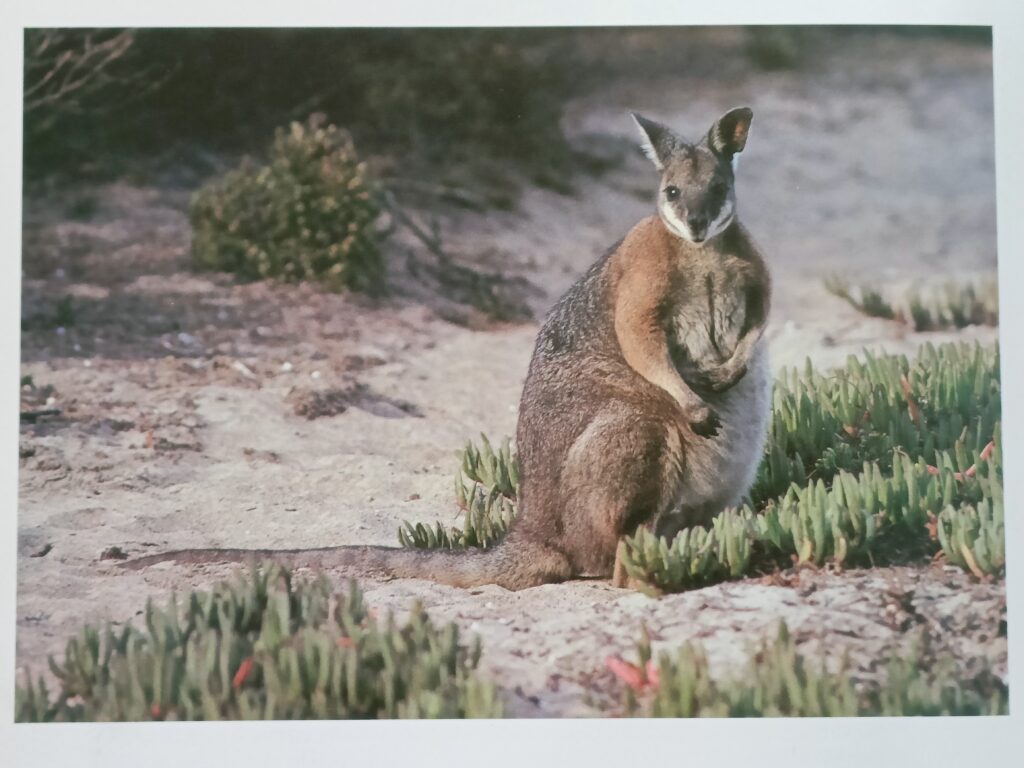

The rather beautiful Swamp Wallaby was known to Kawau locals as the ‘black-tailed’ or ‘walleroo’ – but Walleroos are actually a separate type of kangaroo species. The Swamp Wallaby has an attractive shaggy reddish coat with a dark bushy tail, it has a dark grey to blackish back, a yellow buff belly, a light yellow cheek stripe and orange markings around the base of its ears. It grows to about a metre in height.

Swamp Wallaby (Wallabia bicolor) [photo Jean-Paul Fererro]

The Swamp Wallaby is the only member of the genus Wallabia, most other wallabies and kangaroos belong to the genus Macropus. The swamp wallaby is quite different to other wallabies in regard to reproductive, genetic, dental and behavioural characteristics and while wallabies and kangaroos have 16 chromosomes the swamp wallaby has only 11 (10 for the female).

Its natural range in Australia is the whole of the eastern seaboard from Cape York in the tropical north down to Wilson’s Promontory at the southern-most tip of the Australian mainland, extending into southeast South Australia.

In Australia the swamp wallaby is found in forest with thick undergrowth. On Kawau its preferred habitat is the kanuka scrub at the northern end of the island though I have seen a family, mum, dad and a joey in the pine plantation above Bon Accord Harbour.

Warburton and Sadlier in Caroline King’s Handbook of NZ Mammals report that the swamp wallabies “readily consume toxic species such as bracken (Pteridium esculentum) and hemlock (Conium maculatum), and others high in oil content such as manna gum (Eucalyptus viminalis).” And concluded, “As long as no animals are relocated on to other islands or the mainland, their presence on the island can be regarded as inconsequential.”

Dogs are the main predators of wallabies on Kawau (as they are for kiwi) – but dogs are obviously some way behind humans on this score.

All the Kawau wallabies are now doomed, earmarked for eradication by Auckland Council. Inexplicably rats and stoats without argument New Zealand’s deadliest environmental pest and predators of native birds and reptiles are not the council officers’ priority.

When I was the chairman of the ARC our policy was different. An integrated pest eradication programme, prioritising rats and stoats – and preserving a fenced off population of wallabies, to be treated in the same way as Governor Grey’s arboretum of exotic trees. Sadly, the ARC is long gone and after 163 years in the Hauraki Gulf so too will be the Kawau wallabies.

Mike Lee is the Auckland Councillor for Waitemata & Gulf and a long-standing conservationist. As a Waiheke Islander he first became interested in these members of the kangaroo family resident in the Hauraki Gulf in the 1980s when he was a merchant navy officer in ship’s trading across the Tasman.

[1] There is one more wallaby established in the wild in New Zealand, the red-necked or Bennett’s Wallaby (Macropus rufofgriseus rufogriseus) which is present in the Hunters Hills of South Canterbury and the Quartz Creek district of Southland.

Note the photos by Jean-Paul Fererro are from the book

‘The Kangaroo’

Michael Archer, Tim Flannery, & Gordon Craig.

Publisher Kevin Weldon. McMahons Point NSW. 1985.

This article was published in the October 2025 edition of the Kookaburra.