ANZAC Day address Waiheke Dawn Service: Ormond Burton and his lifelong struggle for peace

We gather here on this ANZAC morning as is our custom every year, to remember those men and women who served their country, especially those who made the ultimate sacrifice.

We do in a troubled and unpredictable world under the steadily lengthening shadow of war.

During the period when we commemorated the centennial of the Great War of 1914-1918, there was considerable scholarly debate between historians on various theories about the causes of the war. While it was universally agreed that the war was a catastrophe, there was no real consensus on what actually caused it.

But by the time the guns fell silent in 1918 more than four years of industrial warfare had killed 15 million to 22 million people with another 20 or so million wounded.

For the British Empire as a whole the number of troops killed was over one million. The Imperial War Graves Commissioner Sir Fabian Ware estimated that if the British Empire dead were to march four abreast down Whitehall, the parade past the cenotaph would last three and a half days.

New Zealand’s contribution to that army of the dead, in proportion to population, was the highest in the Empire. Over 102,000 New Zealanders served in the Great War, some 10% of the population.

Over 18,500 of their young menfolk were killed. Many more were wounded and came home maimed, blind and suffering psychological disorders. Heartbreak and sorrow was visited upon thousands of New Zealand homes, mothers had lost their sons, siblings their brothers, wives had become widows, children orphans. The hopes for marriage, family life and children for thousands of young New Zealand women were ruined because so many young men never came back. The social fabric of the country itself must have been weakened by the loss of some of our best and most courageous young people.

Both the public and the troops were told at the time that this was ‘the war to end all wars’. To the public and the troops this was a proposition entirely believable. Most people found it hard to imagine that something so disastrous, so destructive and in the end so meaningless, would ever be allowed to happen again.

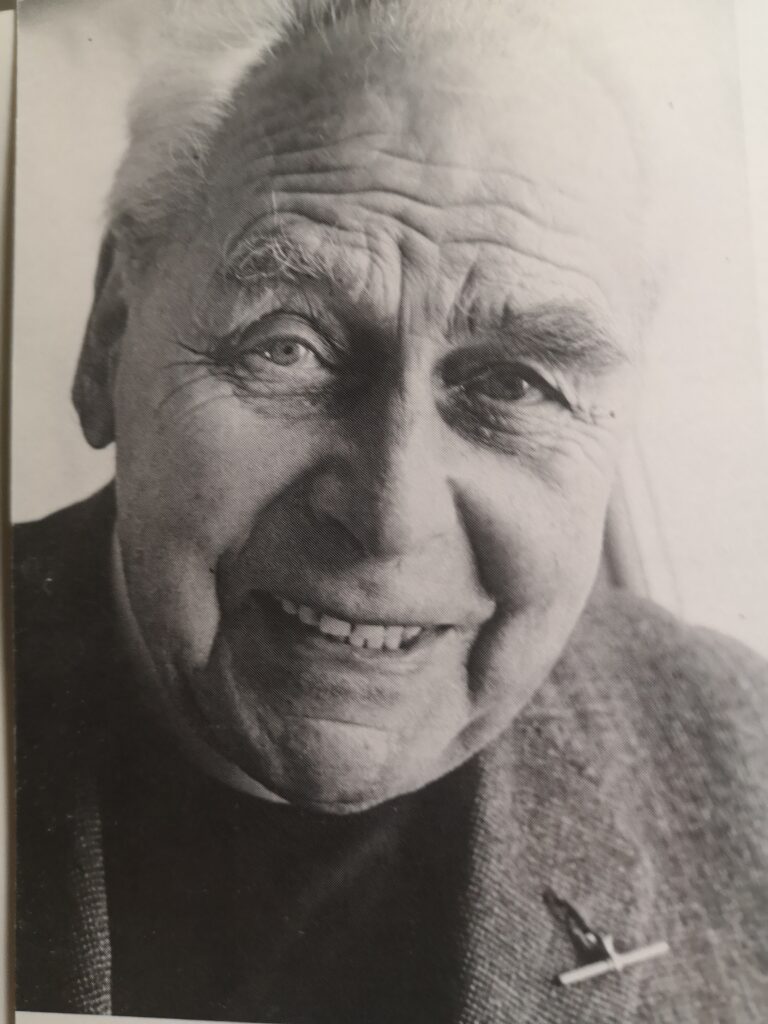

Among those troops was an Aucklander, Ormond Burton. And it is of him I wish to briefly speak about this morning. Ormond Edward Burton was born in Auckland in 1893. He attended Remuera School and then Auckland Grammar. After graduating from Auckland Teachers College he went teaching in remote country schools in the Bay of Plenty.

As an idealistic young man and a committed Christian, like so many he willingly joined the great ‘fall in’ of 1914 and in 1915 served in the No 1 NZ Field Ambulance as a stretcher bearer at Gallipoli

In 1916 along with other Gallipoli veterans he was transferred to the Auckland regiment of the newly formed New Zealand Division fighting on the western front in Belgium and France. The New Zealand Division was soon to become one of the elite formations in the allied armies. Conditions on the western front were considered even more terrible than at Gallipoli.

After a close friend was killed in action Ormond Burton volunteered to take his place in the infantry. At that time he firmly believed the war was a crusade against German/Prussian militarism – a crusade for peace.

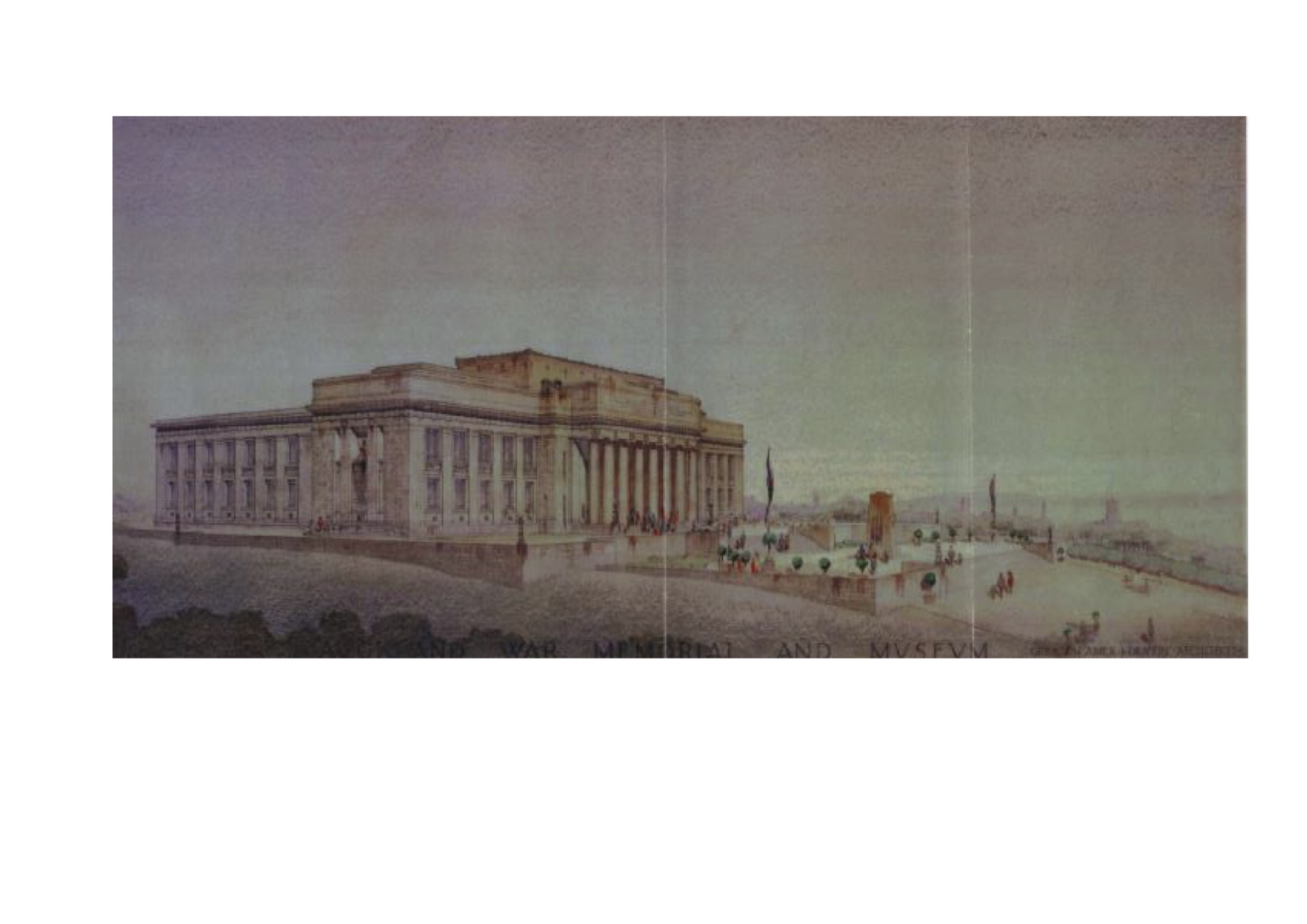

Ormond Burton won the Military Medal for the following action at Grévillers in northern France in 1917 [the name Grévillers is among those carved high on the limestone walls of the Auckland War Memorial Museum building, battles where New Zealand soldiers distinguished themselves].

Here is the citation:

‘Before the company had proceeded 200 yards from the starting point Sergeant Burton took over the platoon, his officer having been wounded, and with remarkable zeal led his men into the front line of the attack.

“On reaching the southern outskirts of Grévillers considerable opposition was encountered and the sergeant was sniped through the wrist. Nevertheless, though this arm was useless, he continued bravely to lead his platoon, and under considerable exposure from machinegun, rifle and shellfire he so advantageously disposed of his men that the ridge running south from the village was firmly secured against the enemy.

“The capture of the six machineguns which fell to the platoon’s lot was mainly due to the bravery and dash of the sergeant. It was not until many hours after being wounded, and when his platoon was firmly established on the ridge that Sergeant Burton was prevailed upon to be evacuated. I would suggest that the NCO be recommended for some decoration.”

Wounded three times but always returning to his unit Burton in 1918 was awarded the Medaille d’honneur by the French government.

Burton’s reputation as a scholar brought him to the attention of the commander of the NZ Division Major-General Sir Andrew Russell. Russell asked Burton to write a short history of the NZ Division. This he did and after the Armistice a copy was given to every New Zealand soldier. At the end of the War he was commissioned as a 2nd lieutenant. But the violence and suffering he had experienced in the war had made him a most resolute Christian Pacifist.

Returning to New Zealand he graduated from Auckland University College with a Master’s degree in History and returned to teaching. But he refused to sign his personal oath as a teacher to the Crown until it expressly acknowledged the primacy of Christ in all matters of conscience. In 1925 he married his wife Nell Tizard. In 1928 he stood for parliament, unsuccessfully, as an independent Christian Socialist for the seat of Eden.

He then worked up his university thesis into a book the ‘History of the Auckland Regiment’, followed by his classic work ‘The Silent Division’. Based on interviews with veterans and his own frontline experience it was published in 1935 with a foreword by General Russell. It is an outstanding book – Burton even managed to find humour in the day-to-day conditions of the fighting men. Military historians consider it the best book on the New Zealand army in the Great War.

Ormond Burton’s spiritual journey led him to train as a Methodist minister and was appointed to a church in Webb Street in Wellington central where he and Nell spent much of their time caring for the down and out victims of the Great Depression – some of them returned soldiers. On Sunday afternoons, Burton, a charismatic orator held open forums at the Basin Reserve where he preached and debated with allcomers – rationalists, atheists, communists and Empire conservatives.

On the outbreak of the Second World War he and two others were arrested for preaching against the war at parliament grounds. He was visited in prison by the deputy prime minister Peter Fraser who pleaded with him to desist. But Burton would not. He was arrested again and again and sentenced to increasingly long periods of hard labour. Offered leniency if he promised to stop his preaching – he refused. Burton had come to the firm conclusion that war was anti-life and therefore an abomination, the sinful destruction of God’s holy creation.

He once told an interviewer:

‘When the First World War ended there came, for many of us, the Great Betrayal. . .The disillusionment was rapid and complete. Victory had not brought a new world, and we saw in a flash of illumination that it never could. War is just waste and destruction, solving no problems but creating new and terrible ones.’

He continued

‘It is now evident that the settlement has not removed any of the causes of war, and that another conflagration is inevitable…

Action is imperative. The future belongs always to the prophets and dreamers, and those who have faith and vision sufficient to be fools for the sake of the kingdom of God.’

Released from prison after the war he obtained work as a night shift cleaner at the Wellington Technical College. Within 10 years he was the principal and proved to be an enlightened and progressive educationalist.

Some of you may be old enough to remember the old man in battered rain coat and clerical collar in the 1960’s and early 70’s, perhaps briefly glimpsed on the television news, megaphone in hand at demonstrations for nuclear disarmament and against the Vietnam War.

Such gatherings were inevitably enlivened by his presence. Sometimes there was pushing and shoving with the police, or as the newspapers termed it, ‘scuffles’.

He was an enormously influential figure in those years, especially with young people. Yet he would always attend ANZAC Day parades wearing his medals, marching with his old comrades. He was in matters of war and peace the conscience of the nation. Ormond Burton passed away in January 1974 praised in the newspapers of the country, as he never was in life – as an authentic New Zealand hero.

So here we are 108 years on amidst the gathering clouds of war. For the first time since the Cuban missile crisis 60 years ago, there is talk of a world war, even a nuclear war.

We can only hope and pray the present generation of world leaders, all of whom have been spared the direct experience of war themselves can make peace before events spiral out of control and into a third world war – a nuclear war which would surely bring the end of human civilisation on this planet.

This nation – this world indeed – no longer has the men of Ormond Burton’s calibre (at least we don’t hear of them) – the ‘prophets and the dreamers’ for peace. We therefore should value even more the legacy he bequeathed to us – and remember his courageous indeed soldierly life-long sacrifice to achieve it.

‘Blessed be the peacemakers for they shall be called the children of God.’

Lest we forget.