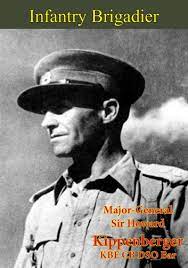

‘Stand for New Zealand! Every man who is a soldier stand for New Zealand!’- Anzac Day 2021 (Dawn service Waiheke Island). Kippenberger’s rallying cry to his troops in the battle for Crete still resonates today.

Today we gather once again to remember the sacrifices of those who served & those who gave their lives for New Zealand, principally in the great world conflicts of the 20th century. The last time we gathered here at dawn in 2019 in the aftermath of the Christchurch mosque attacks I recall we were guarded by police officers with automatic rifles. Last year due to the pandemic for the first time since they began there were no public ANZAC Day ceremonies in New Zealand. Certainly a reminder that we live in a troubled and unpredictable world, where it seems change, not necessarily always for the good, is a constant. Accordingly in this troubled sea of change ANZAC DAY in New Zealand appears to have become a rock of tradition, of continuity, of community unity in the life of our nation.

In past dawn services, especially during the recent years of the Great War centenary, we recalled the heroic sacrifices of the Great War generation. Today I wish to remember the Second World War generation – the generation the Americans now call the Greatest Generation. For people of my age, our parents’ generation.

In regard to New Zealand’s role in the Second World War the historian and economist W.B. Sutch wrote ” NZ had a higher proportion of its citizens in the armed services than any of the other allied powers – apart from the Soviet Union.”

Economic mobilization and a unified national spirit meant that New Zealanders on the home front gave the fullest backing to our young men fighting overseas. As a percentage of national income from 1939 to 1944, New Zealand’s war expenditure was higher than that of Australia, Canada, and the USA and only behind that of the United Kingdom and the USSR.

This economic effort on the home front especially with women stepping into the work force meant New Zealand ended the war with an overseas debt lower by £45 million than it had at the beginning.

Indeed so effective was the home front effort that NZ became a net donor of war aid, not only to the United Kingdom – but also to the United States.

On the fighting front, as with the first New Zealand Division of the Great War, the 2nd NZ Division came to win a reputation from friends and foes alike, as an elite force. Indeed, none other than Field Marshal Erwin Rommel considered the NZ Division to be the best in the British 8th Army.

In May 1941, the citizen soldiers of the 2nd New Zealand Division along with British, Australian and Greek forces, were ordered to defend the island of Crete, hallowed in ancient Greek mythology and literature, against a German invasion.

After days of heavy fighting, German paratroopers seized control of the strategic Maleme airfield. In a battle around the nearby town of Galatas, the NZ defenders came under prolonged heavy attack. Under the onslaught, the exhausted riflemen of the 18th battalion began to fall back. The trickle of men turning into a stream. Had the line collapsed at that point, the Germans would have broken through, imperilling the whole allied position on Crete. The New Zealand commander, Lieutenant Colonel Howard Kippenberger (later Major General) moved among the retreating soldiers, exhorting them to stand and hold – calling upon them to: “Stand for New Zealand! Stand every man who is a soldier! Stand for New Zealand!”

The average New Zealander is not inclined to be demonstrative, (especially of that generation), nor do they tend to be patriots of the hand-on-heart type – and this citizen’s army was no exception. But the evocation of New Zealand and everything that New Zealand stood for in the hearts of those men – rallied them. The retreat stopped – the line held. Indeed the next day, led by Kippenberger the Kiwis counter-attacked and routed the surprised enemy out of Galatas. This action saved the Allied position on Crete, enabling the bulk of the expeditionary force to conduct an orderly withdrawal across the mountains to be evacuated by the Royal Navy to Egypt – to fight another day. It was in the bitter fighting around Galatas that 2nd Lt Charles Upham won the first of his two Victoria Crosses.

John Mulgan was one of this country’s outstanding young writers of the 1930s. Author of the depression-era classic ‘Man Alone’. Mulgan attended Auckland University College as it was called then, then went on to Oxford. Upon the outbreak of war in 1939 he joined the British Army, rising to the rank of Major, and second-in-command of his regiment. Mulgan fought at El Alamein and later as a Greek scholar, led Greek partisans in a guerrilla war behind the lines in occupied Greece, winning the military cross.

Mulgan wrote about this in his book Report on Experience . He also wrote about his impressions of the NZ Division, by then battled-hardened, which he encountered in North Africa.

“Afterwards, a long time afterwards, I met the New Zealanders again, in the desert below Ruweisat ridge, the summer of 1942. It was like coming home. They carried New Zealand with them across the sands of Libya. This was the division that had saved the campaign of 1941 at Sidi Rezegh. The next year, when Rommel came into Egypt, the same division drove down from Syria and up along the coast road against the tide of a retreating army to meet him, and waited for him near Mersah Matruh. They held there for three days. By the evening of the third day, the whole German Afrika Korps, had lapped round them and was closing in. Ordered to come out, the New Zealanders attacked by night, led out their transport through the gaps they cleared, boarded it, and drove back to Alamein. Through all the days of a hot and panic-stricken July they fought Rommel to a standstill in a series of attacks along Ruweisat ridge. They helped save Egypt, and led the breakthrough at Alamein to turn the war.”

“They were mature men, these New Zealanders of the desert, quiet and shrewd and sceptical. They had none of the tired patience of the Englishman, nor that automatic discipline that never questions orders to see if they make sense. Moving in a body, detached from their homeland, they remained quiet and aloof and self-contained. They had confidence in themselves, such as New Zealanders rarely have, knowing themselves as good as the best the world could bring against them, like a rugby team in a more deadly game, coherent, practical, successful.”

“It seemed to me, meeting them again, friends grown a little older, more self-assured, hearing again those soft, inflected voices, the repetitions of slow, drawling slang, that perhaps to have produced these men for this one time would be New Zealand’s destiny. Everything that was good from that small, remote country had gone into them – sunshine and strength, good sense, patience, the versatility of practical men. And they marched into history”

Mulgan also wrote of his idealistic vision for a post-war New Zealand, which sadly he would not live to see. He concluded.

“In this country in a dreamed-of future, men will remember names of desert places that have been dignified by fighting, battle honours of a small country, of that New Zealand of the past, and they will share these things as part of a history that will be dear to them. ‘All earth has witnessed that they answered as befitted their ancestry; they endured as the strong influences about their youth taught them to endure.’”

Perhaps we New Zealanders of the 21st century, should take more time to meditate upon the sacrifices made by our ancestors, our parents, grandparents, great grandparents. To recall the sense of duty, the sacrifices for the common good, the spirit of national unity and national purpose of the New Zealanders of those times – and the high price for nationhood that they paid for all of us.

I have recently been told by a number of historians and history teachers that our secondary school history syllabus is currently being rewritten, and in a way that is likely to produce the bleakest possible interpretation of New Zealand’s history. In a way indeed likely to instil unwarranted guilt, rather than pride, among the majority of young New Zealanders.

We need to ask ourselves, ‘How would those war-generation New Zealanders who believed that the country they knew and loved – to be worth fighting for, even offering up their lives for…what would they make of this? ‘

Rather than rewriting our history to cast our ancestors in the worst possible light, we could be asking ourselves how well have we done? How well have we managed the great patrimony built by the hard work of previous generations and handed on to us? How well have we honoured the unwritten covenant between ourselves and the fallen? But as one Australian commentator has recently written, ‘how can we even hope to be as good as our forbears if we don’t at least remember what they have done’?

In these uncertain, equivocal times, the exhortations of Howard Kippenberger, amid the desperate fighting on Crete, call out to us – “Stand for New Zealand!”

Lest we forget.