The history of marine dumping within the Hauraki Gulf – my submission which helped end the last of it.

IN THE MATTER OF: THE RESOURCE MANAGEMENT ACT 1991 AND

THE HAURAKI GULF MARINE PARK ACT 2000

APPLICATION FROM PINE HARBOUR MARINA LIMITED TO DREDGE SEDIMENT FROM THE MARINA APPROACH CHANNEL AND ENTRANCE AND TO DISCHARGE AND DUMP THIS SEDIMENT, VIA A THIN-LAYER DISPOSAL TECHNIQUE, IN THE BEACHLANDS – HOWICK (WHITFORD) EMBAYMENT.

STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE OF MICHAEL EDWARD LEE

Date: 15 April 2010

INTRODUCTION

1. My name is Michael Edward Lee. I am the chairman of the Auckland Regional Council. My submission is in support of the evidence of the Pohutukawa Coast Community Association. My submission is opposed to the application for resource consents to dump dredged material into the sea in the Beachlands-Howick embayment. In this regard I support the officer’s recommendation to refuse consent for the discharge and deposit of up to 600 m³ of sediment initially, and 500m³ per year (for 20 years) into the embayment. I oppose the officer’s recommendation to grant consent for the discharge and deposit of up to 3000m³of sediment per year from the approach channel (for 20 years).

- My interest in this matter is as follows. I have been actively involved in environmental and conservation issues in the Hauraki Gulf for nearly 30 years. I was first elected to the Auckland Regional Council (ARC) in February 1992. I was elected Chairman of the Council in October 2004 and re-elected to this role in October 2007. Prior to my election to the ARC I served some 20 years in the merchant navy (marine radio officer). I hold an MSc (Hons) in biological sciences (majoring in zoology) from Auckland University. I was a long-time advocate for the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park which was finally enacted in February 2000 and since that time I have been an advocate for compliance with the provisions of HGMP Act. I am deputy chairman of the Hauraki Gulf Forum. I am also a long-standing opponent of marine dumping within the Hauraki Gulf.

- My submission therefore will review the history of inshore marine dumping in the Auckland region. This will have particular reference to public and community responses to marine dumping, as well as the policies and responses of regulatory bodies, especially the Auckland Regional Council. I will also discuss the ARC policies in regard to sedimentation and marine pollution which I believe the reporting officer’s recommendation are in conflict with. Finally I will discuss the wider legal obligations to not only “avoid remedy and mitigate” marine pollution in the coastal marine area (RMA) but to “protect and enhance” the life-supporting capacity, and the physical resources of the Hauraki Gulf which contribute to the enjoyment of the Hauraki Gulf and the wellbeing of the people and communities of the Hauraki Gulf (HGMP).

- My submission will argue that marine dumping in this particular location (more than 60,000 cubic metres over 20 years) is incompatible with any reasonable definition of sustainable management and therefore inconsistent with the provisions of the Resource Management Act 1991, the NZ Coastal Policy Statement and the Regional Plan (Coastal).

- It is also my intention to discuss how this consent is affected by the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act 2000 – (enacted three years after the granting of the last consents by the ARC to Pine Harbour Marina in 1997). I will point out how the HGMP Act changes the regulatory obligations of the consenting authorities with jurisdiction within and around the Hauraki Gulf – as parliament intended. And that therefore the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act cannot simply be dealt with in a superficial way and then effectively ignored. The decision-making process must fully comply therefore with the Resource Management Act and the statutory requirements of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park (including the purposes of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park.

- Finally I note that the ‘History’ section of the officer’s report for this resource consent application overlooks what I believe are important aspects of the history of dredging and dumping by Pine Harbour Marina Ltd in the inner Hauraki Gulf. This historical information I believe is important in providing, the perspective and the context for informed decision making, something which the consultant officer’s report fails to do. This background information I believe is vital in assisting the commissioners in making their decisions in such a challenging and case. The commission must not only consider the physical effects of the activities at issue in this application but also adverse effects on the wellbeing of the community (as noted for instance in the 4th schedule of the Act) as including “effects on the neighbourhood” and “effects on the wider community”. Also bearing in mind s.3 of RMA the Meaning of “effect” the commission needs to consider 3 (b) any past present or future effect and 3 (d) “any cumulative effect which arises over time or in combination with other effects…”

- Therefore it is in regard to the background to this application which I wish to begin my submission. Marine dumping in this area does have a long and troubled history behind it – longer than the history outlined in the officer’s report. Over that time, to use the language of RMA, it has caused significant ‘cumulative effects’. As I see it the consulting officer’s report brushes over this history but it is not forgotten by members of the local community who see the vivid evidence of it in the mud and silt which is continually washed up their once sandy beaches. As Milan Kundera once said “The struggle of people against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”

HISTORY OF DREDGING AND DUMPING IN THE BEACHLANDS – HOWICK EMBAYMENT AND IN THE INNER HAURAKI GULF

4. Marine dredging and dumping is not a new activity in the Auckland region. Auckland is of course a harbour city – a port city. Maritime trade was and almost certainly will always be of vital importance to the economic wellbeing of the city. Auckland is also a major recreational boating centre with hundreds of private boat moorings and 13 small boat marinas. Dredging and dumping goes back to the earliest days of the port on the Waitemata Harbour and indeed the Manukau Harbour.

5. From 1871 the port was developed and managed by the Auckland Harbour Board. The Auckland Harbour Board was founded at the same time as the Auckland City Council. The Harbour Board was dis-established in 1989 when its commercial responsibilities were assumed by the new port company Ports of Auckland Ltd and its regulatory role by the Auckland Regional Council.

6. Though complete records have not been kept it is estimated that over 6 million cubic metres of harbour floor dredgings have been uplifted and dumped into the inner Hauraki Gulf over the past 100 years and another estimated 7 million dredged and used for reclamation purposes.[i] (please note including dredgings which since 2001 are being placed within the Fergusson container terminal expansion).

7. Natural background sedimentation of the coastal marine area has been multiplied many times over in the last 50 years in particular by sediment run-off, especially as a result of large-scale earthworks especially relating to suburban and coastal subdivisions. This human-induced sediment run-off is believed to contribute to a significant degree to harbour siltation – including the siltation of marinas and therefore to the material that needs to be routinely dredged. In addition poorly planned and sited modifications to harbours and estuaries such as reclamations and marinas can change natural hydrology, current flows and bathymetry which can exacerbate the sedimentation problem. Unfortunately the location and design of Pine Harbour Marina and its approach channel based on the empirical evidence of the past 22 years appears to be a classic example of this.

8. Some of this sediment run off is “clean” but much of it is contaminated with pollutants such as heavy metals, biocides and PAH. Long term monitoring by the ARC has identified that Auckland has a major and growing problem with the accumulation of heavy metals in the inner harbour.[ii]

9. ARC studies also indicate that in addition to contaminated sediment, ‘clean’ sediment such as fine colloidal clays can also have a significant adverse effect on the life supporting capacity of the marine environment – damaging the benthic environment and benthic taxa and increasing water turbidity, reducing clarity (even modifying temperatures) and therefore the health and the life-supporting capacity of the water column.[iii] As Dr Bob Dray from the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries pointed out at a previous Pine Harbour consent hearing in 1999 “sediment itself is a contaminant.” Hence the considerable effort the ARC puts into reducing sediment run off ‘clean’ or contaminated from construction activities, subdivision earthworks, forestry, road building etc.

10. I would here make the self-evident observation that the ongoing disturbance of the sea bed and the broadcast of silt (whether ‘clean’ or contaminated) from one part of the Beachlands-Howick embayment and its disposal through the water column of another part of the embayment accumulatively compounds a significant local marine pollution problem.

The Browns Island Dumping Incident

11. Up until 1989 the Auckland Harbour Board as the owner and operator of the ports of Auckland was the principal participant in dredging and dumping activities. Routine dredging was required to keep the berth space alongside the commercial wharves and shipping channels at chart datum level. Prior to 1988 two disposal sites were in routine use. The main site was on the northwest side of Rangitoto Island with a secondary occasionally used ‘foul weather’ or emergency site just to the northeast of Browns Island.

12. The disposal of maintenance dredgings into the inner Gulf continued routinely, and without public objection or controversy, until early in 1987 when a dumping permit was granted by the Ministry of Transport (Marine Division) for the use of the Browns Island ‘emergency’ site for the dumping of 147,000 m³- of material produced from excavation works from marina construction. Dumping commenced over this site in March 1987 and continued until November 1987. This activity became controversial when the visible environmental effects of the dumping became significant enough to draw complaints from recreational and commercial boat owners and fishers. As a result there was considerable media coverage in the Auckland Star, NZ Herald and the Howick and Pakuranga Times which in turn led to a public outcry. In hind-sight the unfortunate result was inevitable. A shallow water location (5 – 7 metres) previously used for the occasional disposal (one or two barge loads per year) [iv]of maintenance dredging was mis-used for the intensive dumping of a very large amount of what are called capital dredgings. Some of the dumped material came from the construction of the extension of Bucklands Beach Marina – but the bulk of it came from the construction of Pine Harbour Marina – the same Pine Harbour Marina which is the subject of the application here to day.

- Marine dumping, previously ‘under the radar’ had now become a major public issue. The companies involved however were not deterred and the dumping of dredgings from Pine Harbour Marina was only finally halted after legal action was threatened by the Environmental Defence Society. A Pine Harbour Marina Ltd company spokesman (general manager David Whitfield) announced that the company would dispose of future dumping on land rather than in the harbour. (New Zealand Herald 16 December 1987). However it was apparent by then that the company had disposed of all the material it needed to.

- At the request of Auckland Harbour Board members led by Allan Brewster, a prominent recreational boating advocate, an ecological survey of the site was carried out by Dr Roger Grace. It should be recalled that the responsibilities of the Auckland Harbour Board were wider than the strictly commercial role of the post-1989 port company. The Harbour Board also had environmental management and recreational boating responsibilities. Dr Grace’s survey found significant damage to the sea bottom within the 21 ha dump site, extending over a widespread area (150 ha) around the dump site. There was a 97% loss of marine life recorded within the dump site where discharged mud had covered the sea floor to a depth of 600mm. There was also clear evidence of lighter material being transported off site. [v]

- Given the shallow depth of the site, 5 -7 metres, the movement of material off site especially from wave action after storms, movement off site would be inevitable.

- As has been noted the Browns Island site had previously been used only occasionally and in bad weather. Why was this site sought for use rather than the regular deeper water northwest Rangitoto site? It appears that dumping at the Browns Island site which is only about 6 nautical miles from the Pine Harbour Marina was simply more economic than transporting the material the extra distance (about 14 nautical miles) to main disposal site to the north of Rangitoto. And of course it was much cheaper than disposing it in a clean fill where clearly much of this excavated material should have been placed.

- As a result of the public outcry set off by this marine pollution incident, the Auckland Regional Water Board (an agency of the then Auckland Regional Authority) belatedly emerged onto the scene and announced that in future a formal ‘water right’ consent would have to be applied for, for any future dumping citing the provisions of the Water and Soil Conservation Act 1967. At the same time a conference was called by the Ministry of Transport involving the Auckland Harbour Board, the Auckland Regional Water Board, the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries and the Department of Conservation. As a result of this conference the Harbour Board agreed to end dumping at the Browns Island site and also agreed to investigate a new deeper water dumping site further out in the Hauraki Gulf.

- In 1989 the Auckland Harbour Board was disbanded and replaced by the newly formed Ports of Auckland Ltd. Unlike the Harbour Board the new POAL had a purely commercial focus. In the meantime the Browns Island marine pollution controversy caused by the Pine Harbour dumping and its consequences resulted in a suspension of maintenance dredging of the shipping berths in the port of Auckland and therefore causing a backlog.

The Ports of Auckland application to dump 12 million m³ of dredgings off the Noises Islands 1990

- In order to deal with this backlog, first of all the newly formed Ports of Auckland was required to identify a new dumping site. After a process led by its expert advisers, principally the consultants Kingett-Mitchell and Associates which lasted six months and cost the Port Company nearly one million dollars a site 3km north of the Noises Islands and 7 km southeast of Tiritiri Matangi Island was selected. The issue again became highly controversial when it was announced that the Port Company needed to dump a massive 12 million cubic metres of dredgings over 15 years at the new site. The proposed disposals were to be made up of 11.85 million cubic metres of capital dredgings (from the deepening of the Rangitoto channel) and 270,000 cubic metres of maintenance dredging from the backlog essentially caused by the moratorium brought by the Pine Harbour – Browns Island dumping incident. That the Noises site in question was a well known snapper breeding area added to the level of public controversy.

- The ‘water right’ application made under the Water and Soil Conservation Act (this was pre RMA) was heard by a hearing panel of the Regional Water Board in October 1990. The Port Company’s application was opposed by 25 objectors including Auckland City Council, NZ Underwater Association, the Inshore Commercial Fishermans Association, NZ Fishing Industry Board, Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society, Greenpeace, amongst others.

- The objections can be summarised as follows:

- The large volumes of sediment to be disposed of would smother benthic sea life, enter the water column and cause widespread death and destruction to marine organisms in what was until then a pristine seabed site

- That contrary to the claims of the Port Company’s scientific and technical experts, the site was not a “containment site” and therefore large amounts of sediments would migrate off-site, pollute nearby reefs and add to the sediment loading of inner Hauraki Gulf waters.

- That heavy metals and chemical toxins known to be in the Harbour sludge especially around the Wynyard tanker wharves would enter the food chain

- That these effects would adversely effect an important snapper breeding ground and a valuable commercial and recreational fishery and;

- That the dumping of land derived sediments into the ocean was contrary to Maori spiritual beliefs and cultural value and contaminate a traditional Maori sea food area.

(It is important to note that no serious argument was made against the need for dredging the port itself. Routine maintenance dredging was recognised by all parties as essential to the operation of the port. The issue of contention was purely disposal of those dredgings into the marine environment. )

- The decision of the Hearing Panel was to grant a water right consent for the disposal of 270,000 cubic metres of maintenance dredging but the commission declined to make a decision on the 11.85 million cubic metres of capital dredging and recommended a separate hearing. The consent was subject to a number of conditions – the most interesting being a requirement to suspend dumping from November to January due to the snapper spawning season. This was made at the request of Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. The decision was appealed to the Planning Tribunal by a number of parties. However legal manoeuvring and fears about costs and punitive damages meant that only a small group of appellants remained when the Tribunal convened in July 1991. The appellants were the NZ Underwater Association, supported by the Marine Transport Association, with the Hauraki Maori Trust Board and Greenpeace as interested parties.

- As an interested private citizen (this was before I was a member of the ARC) I was an observer at the Planning Tribunal appeal and was surprised and frankly disappointed to discover that despite the existence of numerous government and local government agencies and conservation organisations (eg DoC, MfE ARC and ACC and Forest and Bird) charged with protecting the marine environment, the full burden of the appeal had been left to the NZ Underwater Association represented by a recreational diver from Wellington Mr Max Heatherington. Mr Heatherington was supported by Mr Keith Ingram of the Marine Transport Association and a fellow diver Mr Bruce Carter. A highlight of the case was an impassioned plea in Maori against the dumping by the paramount chief of Ngati Maru Toko Renata te Tanwiha – a witness for NZUA. Despite this the appeal was dismissed. An appeal on a point of law was taken by the Hauraki Maori Trust Board to the High Court but was ultimately not pursued.

POAL dumping off the Noises 1992

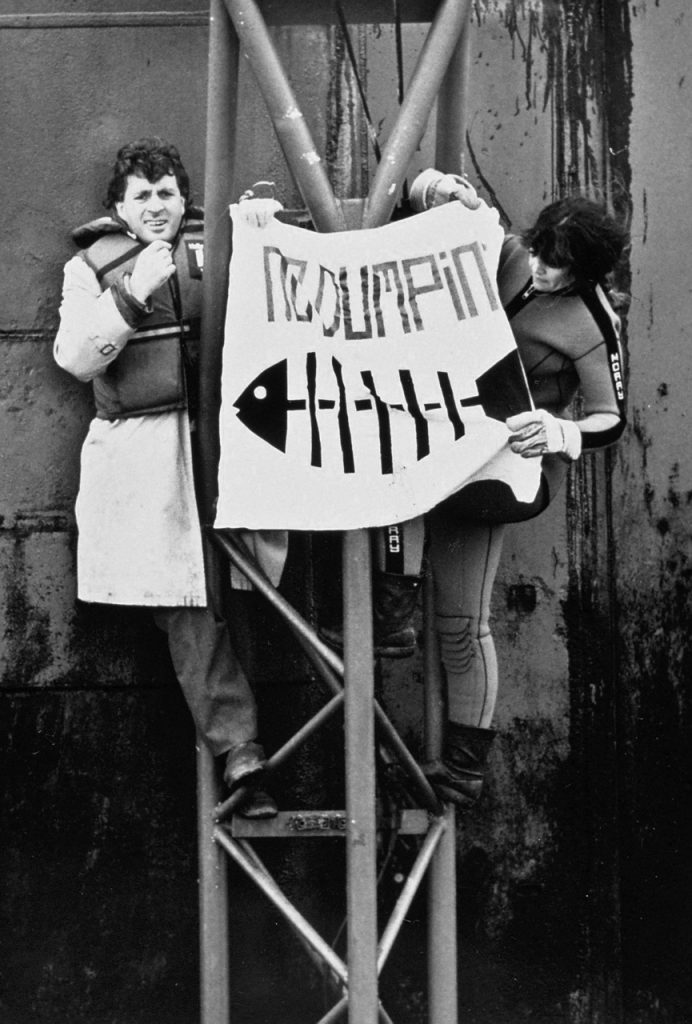

- Dumping finally went ahead in late August 1992 amidst widespread public protests. So widespread was the opposition that Greenpeace International diverted one of its ships MV Gondwana to Auckland to help organise protest action. I by then had been elected to the Auckland Regional Council and I was asked by Greenpeace take part in a direct protest action off the Wynyard tanker wharf (Wynyard Point and the adjacent CMA is now recognised as a contaminated site) with three Greenpeace activists in which I was arrested for the first and only time. However we had made our point and fortunately the court was lenient.

- The controversy did not end there. The Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment Mrs Helen Hughes became involved. The Commissioner set up a Technical Review Panel to review the monitoring programme established as part of the conditions of consent. The findings of the report released by the Parliamentary Commissioner in 1995 were contradictory. On the one hand hand it supported the Ports of Auckland consultants’ contention that “the disposal operation has not caused any significant impairment of ecological systems in the Hauraki Gulf” but it also conceded that “ecological data gathered at the Noises Islands was difficult to interpret due to large natural variability and confounding effects such as the extend El Nino during 1992”. [vi]

- Most damagingly it did disclose that contrary to POAL expert advice “25% of the disposed sediment had dispersed from the site”. [1] The Parliamentary Commissioner’s report noted. “The cause of the loss of sediment from the site has been attributed to a larger than expected water content in the dredge spoil, associated with the operation of the dredge. Measurements after disposal showed that the fluidised sediment spread over a much wider region than expected. The evidence at the Planning Tribunal predicted that the spoil would form a mound some 9 m high. After horizontal spreading, the mound actually extended .9 above the natural seafloor bottom. With a high fluid content, spoil is more easily lost during disposal and more easily entrained by storms during the compaction period.” In other words the Ports scientific experts and the Regional Water Board (ARC) officers’ confident predictions were proven wrong. In relation to the spread of contaminated material, the report expressed concern about elevated levels of DDT at three sites to the south of the disposal zone and one ‘control’ site to the west.

- However the movement of some 86,000 m³ of sludge (according to an ARC report of September 1993) much of it contaminated, off site and into the water column only confirmed the predictions of the critics of the dumping including Dr Peter Balance of the Geology Department Auckland University (Dr Balance passed away last October). In a letter to the NZ Herald Dr Balance wrote “The Ports of Auckland Company is apparently surprised that the harbour dredgings dumped in the Hauraki Gulf are not staying precisely where they were put. Did anyone seriously think they would? Do people really think the Gulf is a dead place where nothing moves? Quite the contrary, the Gulf is a dynamic place. Organisms stir the sediment, waves and tides move it around. The dumped area is in water just over 30m deep. Waves stir the bottom at a depth equal to half their wave length so swells more than 60m apart will move the dumpings. It is quite extraordinary what a simplistic view many planners and engineers take of natural processes…Nature is nothing if not complicated and it is surely time we recognised the fact.”

- The embarrassed ‘experts’ suggested that perhaps “compaction” of the sea-bed might explain the huge discrepancy but the ‘non-expert’ Mr Heatherington of the NZ Underwater Association pointed out to the NZ Herald that “the amount of dumped spoil was measured as it was dredged from the port and if 262,000 cu m was dredged, it should be still at the site even with consolidation.”

- As a postscript in March 2008 I was inspecting the Noises Islands with its private owners Mr Rod Neureuter and his sisters Sue and Zoe. The Neureuters, whose parents owned the Noises and who have had a lifetime experience of the islands, observed that after the 1992 dumping and for many years subsequently high levels of fine sediment were observed in the waters around the islands with a noticeable reduction in water clarity. The dumping in the Spring of 1992 coincided with their subsequently noting the disappearance of kelp and seaweed beds from around the island and also the disappearance of small rock pool fish. Happily 12 years after the dumping water clarity, kelp and small fish have recovered – but according to Mr Neureuter and his sisters not to the level remembered by the family before the dumping. Biocides including TBT and DDT were known to be in the 262,000 m³ of material dumped in the area. These eyewitness reports are of course anecdotal and these people are not ‘experts’; but on the other hand they are intelligent practised of observers of their islands’ environment. They have no particular axe to grind and there is no reason to doubt their honesty or observations. And as I shall demonstrate in my submission, paid experts have been proven wrong on numerous occasions on issues of crucial importance relating to marine dumping.

The DOAG process and agreement of future dredging disposal

- Meanwhile another major consequence of public opposition to dumping in the Hauraki Gulf was for the Ports of Auckland and all the other interested stakeholders including the ARC, Auckland City Council, other city councils, conservation groups, and harbour user and boating groups to form a Disposal Options Advisory technical Group (DOAG). The technical group chaired by retired judge, Dame Augusta Wallace met on 18 occasions over the period 7 July 1993 to 19 October 1994. During its deliberations all options in regarding to disposal of dredgings were examined and a robust solution to the problem of marine dumping was eventually formulated by agreement between the parties.

- During the DOAG process Ports of Auckland reassessed its capital dredging calculations and radically reduced the amount from the original 11.8 million m³ to 6.7 million m³ — just over half!

- The DOAG final report concluded that should marine disposal of dredgings be necessary it would prefer to see disposal moved away from the controversial disposal site adjacent to the Noises Islands. Of the two areas identified by the DOAG evaluation, the majority of the group preferred that disposal take place in water deeper than 100m over the continental slope outside the Hauraki Gulf north of Cuvier Island in an area traditionally used by the navy as an explosives dump site.

- A minority of the Group found disposal within the Hauraki Gulf at a site near Kawau Island acceptable.

DOAG Summary and Conclusions

The DOAG agreement was ratified by all the major dredging agencies at the time (except Pine Harbour) and it now has statutory recognition in the Regional Plan (Coastal) – the agreement is as follows.

- If dredged material is disposed of in the harbour edge environment, the group recommends that dredging be placed into Port reclamation.

- Land disposal provides opportunities to return sediment to the land (for example, highly contaminated maintenance dredgings to sanitary landfill), or to find beneficial uses for it.

- The group considers that, if marine disposal was continued, it would recommend disposal move to a site northeast of Cuvier Island which is located in more than 100m of water (known as the AEDG – the Auckland Explosives Dumping Ground).

- The consequences of the above conclusions and recommendations are that the technical group gives preference to the following disposal options for the following categories of Port dredgings:

- For highly contaminated dredged material. i) Port Reclamation ii) Approved sanitary landfill

- For maintenance dredgings that meet regulatory guidelines: i) Port reclamation ii) Marine disposal in water deeper than 100m

- For capital works dredgings:

- I) Port reclamation or ii) Marine disposal in water deeper than 100m

The Regulatory Response – Regional Policy Statement and Regional Coastal Plan

- Another consequence of the widespread public opposition to marine dumping in the Hauraki Gulf was the regulatory response taken by the ARC from September 1992 – to mid 1996. The Report of the Disposal Options Advisory Group – Part 4 – refers to this.

- In essence the ARC policy response was initiated in September 1992 during the last months of what was essentially the 28 member ‘ARA’ incarnation of the Auckland Regional Council. At this time a resolution signalling a policy of opposing dumping was carried by a large majority of members. The resolution was as follows:

- That this Council duly recognising:

- that New Zealand has become a signatory to the London Dumping Convention;

- The widespread public opposition, including the tangata whenua to marine dumping in the Hauraki Gulf;

- The Auckland Regional Council’s support for a Marine Park in the Hauraki Gulf which would enhanced the status and protection of the area;

Hereby resolves to notify the Resource Policy and Planning Committee of the Council’s wish to include in the Regional Policy Statement and Regional Coastal Plan a policy of clear opposition to the dumping of future dredgings into the waters of the Hauraki Gulf.

- The ARC produced a “Discussion Document” in October 1992 to inform the public of the RCP process and what were then current ARC thoughts on the main issues and options for addressing them. However the 1992 Council resolution and its implications for the RPS and RCP were not referred to when ARC officers reported on these documents to the new 13 member Council early in 1993. Despite this officer oversight the members of the new ARC formally confirmed the 1992 resolution anyway and officers were instructed to proceed on this basis. A “Summary and Analysis of Submissions” received from the public in response to the Discussion Document was produced a year later in September 1993. A total of 80 submissions were received on the subjects of “Dredging and Disposal.” According to the DOAG report “a large majority” supported the new ARC policy. The policy was incorporated into the “Proposed Regional Policy Statement notified in May 1994.”

- Specifically this was:

“Policies 8.4.22 Disposal of dredged material

The ARC opposes the disposal of dredged material, or other solid matter likely to cause significant adverse effects on the environment, to any part of the CMA of the Hauraki Gulf.

Methods:

8.4.23

The Regional Coastal Plan will contain a rule prohibiting the disposal of dredged material, or other solid matter likely to cause significant adverse effects to the environment to any part of the CMA of the Hauraki Gulf.

This policy was also reflected in the draft “Auckland Regional Coastal Plan” which was printed on 12.9.94. and I quote Chapter 6.0

Disposal of Dredged Material and Deposition of Other Solid Matter

Policies

The marine disposal of dredged material into the CMA of the Hauraki Gulf should be avoided

and

Prohibited Activities

The Marine disposal of dredged material, regardless of the degree of contamination, to any part of the CMA of the Hauraki Gulf.

- So to summarise the situation – by 1995 the major organisations involved with dredging and dumping, notably the Ports of Auckland Ltd and all of the other marinas – on the basis of a strong public consensus had worked through a process which led them to an agreement to in future restrict the disposal of dredgings to contained reclamation work or to dispose of the material outside the Hauraki Gulf at the deep water AEDG dump zone northeast of Cuvier. Contemporaneously, in parallel with the DOAG process, the ARC recognizing the special nature and status of the Hauraki Gulf and public attitudes towards it (which was in the process of becoming a Marine Park), in its proposed Regional Policy Statement and draft Regional Coastal Plan, had made marine dumping in the Hauraki Gulf a prohibited activity.

Pine Harbour dredging and dumping

- Very soon after completion of construction of Pine Harbour Marina in the late 80s its owners were to discover that contrary to the advice of their engineering experts, siltation of the marina and its approach channels was a much more significant problem than had been predicted. As noted by one of Pine Harbour’s later scientific consultants, Professor Terry Healy, when Pine Harbour Marina was constructed in 1986 the original environmental assessment report (Wilkins and Davies 1985) asserted that the deposition in the channel would be such as to require dredging only about once in every 20 years. However within 2 years the Marina experienced sedimentation that affected navigation in the approach channel.

Pine Harbour 1990 illegal dredging and dumping

- After the Browns Island dumping incident in 1987 when Pine Harbour Marina Ltd were finally deterred from further dumping by the threat of legal action, as we have previously noted, a company spokesman (general manager David Whitfield) announced that the company would dispose of future dumping on land rather than in the harbour. (New Zealand Herald 16 December 1987).

- However in 1990 the company began dredging and dumping in the CMA in the Whitford estuary without a consent. A back-hoe excavator mounted on a barge was used to dredge the approach channel. Dredged material was then side-cast onto the intertidal flats inshore of the channel. No approvals were given for this work and no monitoring was carried out. The activities were finally halted by the Minister of Conservation but by then the works were essentially complete. No action was taken against Pine Harbour Marina Ltd by the ARC or any other regulatory agency for this unauthorised activity.[vii]

Pine Harbour consented dredging and dumping from 1993

- In 1993 Pine Harbour Marina Ltd applied to the ARC for permits to dredge up to 4,500m³ of sediment from the approach channel and to dispose of the material by side-casting onto the northern side of the channel. Despite the predictions of Pine Harbour’s technical advisers much of the material that had been previously (and illegally) excavated and dumped on the southern side of the channel had quickly found its way back into the approach channel. So this time the technical experts advised dumping on the northern side of the channel.

- The application in late 1993 was made while work was underway through the Regional Policy Statement to effectively end dumping in the Hauraki Gulf. Though most public attention was on the bigger POAL dredging and dumping issues (then being worked through the DOAG process) as usual there was significant opposition from the local community to Pine Harbour’s proposals (not to the dredging but to the dumping). Despite this strong local opposition, the case took place as it were ‘under the radar’. Approvals were granted though the ARC officers’ report noted. “It was uncertain whether the sediments would harmlessly enter back into the naturally occurring movement of sediments within the embayment, whether it would significantly effect the local ecology, or whether it would be the source of muddy deposits along the Beachlands Maraetai or Howick beach frontages.”[viii]

- Some time in 1996, (after the 1995 local body elections at which a number of environmentally-minded ARC members including myself were thrown out) a more politically conservative ARC changed the proposed Regional Policy Statement and the draft Regional Coastal Plan to remove the prohibition on dumping within the Hauraki Gulf (despite the widespread public support for this measure). The Regional Plan (Coastal) as it was now called instead making dumping in the Hauraki Gulf a discretionary activity.

- Shortly after this in 1997 Pine Harbour Marina Ltd went back again to the ARC with a consent application for more dredging and dumping. Because of the obvious failure of the side-casting method of disposal – both to the south of the channel and to the north of the channel, Pine Harbour Marine Ltd experts led by Professor Terry Healy proposed another method of getting rid of dredged material – “thin layer disposal.” It was argued that scattering this material over a larger area would have less environmental effect, than previous dumping efforts. However it is fairly clear the Company decided on this approach because previous efforts at side casting (authorised to the north and illegally to the south) had failed to keep the channel clear. Thin layer disposal it was argued would be the answer. However environmentalists believed that scattering this material over a wider area would merely add to the sediment loadings of the water column – and over a wider area. This is what many local residents thought as well, as did the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries when it opposed the consent. These concerns were dismissed by the ARC officers and the ARC hearing panel. Despite the strong local opposition the company was granted resource consent by the ARC to undertake 3000 m³ of dredging per annum for 15 years i.e. up to 45,000 m³ and to dump this material in the Beachlands-Howick embayment for a period of 10 years.

- (This dumping permit expired on 31 December 2007 and was unfortunately been effectively renewed on a non-notified basis by the ARC Group Manager Consents and Compliance Water – for another 20 years. This was based on the questionable legal advice that the ARC officer in question had no option but to do so. It would appear that this 20 year non-notified renewal to dump up to 60,000 m³ more material in this embayment despite strong public opposition can now only be over-ruled if this hearing commission declines the present consent application and all appeals are exhausted).

1999 Pine Harbour’s ‘Reagitation Dredging’ Application

- In 1999 when Ports of Auckland and the other marinas were complying with the DOAG consensus by disposing of dredgings at the deep water site, Pine Harbour came back to the ARC for yet another consent. This time their expert advisers led by Professor Healy had proposed yet another even cheaper method of dredging and dumping – specifically for the marina itself which was experiencing sedimentation problems. Though this marina sediment was clearly known to be contaminated Professor Healy proposed a new technique known as ‘re-agitation dredging’ which involved stirring up the sediment and allowing the resulting plume of suspended contaminated mud to be sucked out on the outgoing tide ideally to be dispersed in deeper water – far away. Of course Professor Healy and the other Pine Harbour expert advisers as usual supported their proposal with a great deal of technical evidence. But behind the so-called ‘scientific’ arguments advanced by these people – ‘re-agitation dredging’ was just a cheap way of replacing mechanical dredging and the need for deep sea or land-based disposal of the contaminated material – and an environmentally irresponsible one at that.

- Again the local community and the Ministry of Fisheries vehemently opposed this application with rather devastating common-sense submissions. Despite ARC officers supporting the application, the ARC hearing panel chaired by my predecessor Cr Gwen Bull agreed with the community and declined the consent.

- Unfortunately, after Pine Harbour Marina Ltd appealed the decision to the Environment Court, ARC officers, without the knowledge or assent of the Hearing Panel, agreed to allow the company to undertake a trial using the re-agitation method. As the officers’ report to this consent blandly recounts. “The method was not consented for a volume of 10,000 m³, but a lesser (900 m³) was consented to assess the effects of the methodology.”

- The officer’s report to be kind, is rather economical with the truth here. What the report does not say is the officers’ consent for nearly 10% of what the company had originally asked for effectively undermined the decision of the hearing panel and therefore made a joke of the public process – (it also would have compromised the Council’s legal position had the appeal finally gone to court). However despite Professor Healy’s expert arguments – the trial which used a tracer dye proved to be an embarrassing failure. The tell-tale tracer dye revealed contaminated marine sludge was spread around the estuary, into the CPA (Coastal Protected Area) 1, over the ASCV (Area of Significant Conservation Value) shellbank and the foreshore, just as the non-scientific opponents in the local community predicted it would. Pine Harbour Marina Ltd then quietly dropped its appeal to the Environment Court. However as a result of this unauthorised action by ARC officers and a similar one some time later, the ARC committee delegations were changed in 2004 during the time of Gwen Bull’s leadership, to require officers to report back to the Environmental Management Committee if officers wished to change hearing panel decisions as a result of subsequent legal or other developments.

The role of ‘technical experts’ in marine dumping

- I note how much the role and importance of experts has been emphasised by the applicant in this case. It as if there are two hearings – one for the ‘experts’ and one for ordinary folk. Such elitism does not fit well with our British system of justice (and this is a quasi-judicial process). The RMA makes no mention of ‘experts’ as such but repeatedly refers to the rights and aspirations of “communities” and “people” and the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act emphasises the rights of “people and communities” even more. So it is important that we resist an incipient elitism which attempts to marginalise citizen not considered “experts”, in the RMA process. Indeed when one examines the unhappy history of inshore dumping in this area – the role of ‘experts’ is not exactly inspiring of confidence. The opposite in fact

- Reviewing this history over the last 25 years or so, a number of patterns become apparent. These patterns are quite clear despite the fact that interestingly enough since 1988 all the major regulatory agencies have changed along with their names. The ARA Regional Water Board is now the Auckland Regional Council, the Auckland Harbour Board is now the Ports of Auckland, the Planning Tribunal is now the Environment Court, even the Maraetai Ratepayers Association is now the Pohutukawa Coast Community Association.

- I would note the legislation has also changed since the late 1980s. The role of the Marine Pollution regulations were at first superseded by the Water and Soil Conservation Act 1967, which in turn was replaced by the Resource Management Act 1991 and also for nearly 10 years now the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act 2000. In fact just about everything has changed except for Pine Harbour Marina Ltd and its modus operandi which is based upon a strongly held sense of entitlement for that company to use the inner Hauraki Gulf as a cheap, convenient dumping ground. That Pine Harbour is the only ‘odd marina out’ in persisting with inshore dumping is very fortunate for the rest of Auckland but not much consolation for the people who live along this coast.

- The company’s continued use of the Beachlands-Howick embayment is remarkable in itself but its successful strategy has been achieved by aggressive lawyers and justified by voluminous evidence by paid consultants and technical experts. This has been a very effective approach in convincing the authorities (except on one notable occasion) to over-ride the legitimate (and very rational) concerns of the local community, and to persuade council officers and consenting authorities to go against the international trend of protecting sensitive coastal waters from marine dumping.

- In the review of marine dumping that I have outlined, I have concluded that the Ministry of Transport was will within its rights in 1987 to prevent Pine Harbour Marina developers dumping a huge amount of excavation spoil over the Harbour Board emergency site at Browns Island – but they choose to consent to this because technical experts assured them that the site could safely accommodate the huge amount of material.

- The Regional Water Board and the ARC had every legal right under the Water and Soil Conservation Act to direct the Ports of Auckland to dispose of maintenance dredgings either as reclamation or in deep water offshore (as eventually happened anyway). But Ports of Auckland technical experts and ARC Water Board scientists claimed the Noises site was a safe ‘containment site’ and argued that the harbour dredgings were clean.

- The ARC hearing panels in 1993 and in 1997 had every legal right under the Resource Management Act to decline Pine Harbour’s application to dump in the estuary and to direct Pine Harbour to comply with the DOAG consensus and yet they did not. On each occasion Pine Harbour Marina Ltd’s technical experts, supported by Council officers persuaded commissioners to dismiss the logical objections of local residents on grounds of ‘science’ or ‘expert technical advice’.

- This often voluminous technical evidence which would on the face of it would have been impressive in appearance and scale and was delivered by confident professional people – more impressive than that of the submissions of the ordinary members of the public. For instance as the NZ Herald noted this unlevel playing field which developers and ordinary members of the community must contest upon in November 1990 during the application by Ports of Auckland. It noted “Ranged against the volumes of official reports were one and two-page documents, some even hastily handwritten.”

- And yet time and time again the paid experts got it wrong. A classic example in 1990 POAL’s consultants argued in some detail that 12 million m³ needed to be dredged and dumped (11.8million m³ of this from lowering the depth of the Rangitoto shipping channel). During the DOAG process Ports of Auckland revised the amount down 6.7million m³. The amount eventually need to be removed was actually only 830,000 m³ (which went into the Fergusson wharf reclamation) – a figure of almost exactly 11 million m³ less than the amount argued for by experts in the November 1990 hearing – in other words 7%. They were 93% out. This is an astonishing disparity but illustrates how in this sort of highly adversarial process how the expert evidence cannot always be accepted at face value.

- The Port’s experts also argued that the Noises site was a ‘containment site’ and yet we know that in the face of their confident predictions about at least a quarter probably a third of the material was resuspended and spread around the Gulf.

- Coming back to Pine Harbour Marina we have also seen repeatedly how the experts got it wrong. Wrong about side-casting to the south, wrong about side-casting to the north, how compliant ARC officers allowed them to have a trial to prove their expert opinions on ‘re-agitation dredging’ and how they all got that wrong as well. And I am absolutely convinced that the local community is right in their belief that once again the paid experts are wrong about the significant adverse effects that thin-layer disposal has had, is having and will have over the long term on the sensitive marine environment of the Beachlands-Howick embayment. What is remarkable to me commissioners, is to my knowledge not one of these paid experts, nor the company which paid for them, has ever apologised to ordinary citizens for the mistakes they have made at the expense of the marine environment.

- Perhaps however the most significant error committed by the experts goes back to the very beginning of this saga when Pine Harbour Marina Ltd was convinced by its own experts that the approach channel would only have to be dredged once or twice every 20 years – instead of at least every 3 years. How could they get that so wrong?

- But perhaps there is an explanation for at least this major miscalculation. I referred earlier to Pine Harbour’s involvement in large-scale dumping of 147,000 m³ of capital dredgings off Browns Island. In a report for Pine Harbour Marina Ltd dated 17 June 1994 the consultants Kingett Mitchell (who of course had been the advisers to Ports of Auckland) in discussing the unexpected siltation problem with the Pine Harbour Marina approach channel which lies just 5 nm to the southeast suggested that the “dredged material dumped near Browns Island could have become mobilised and drifted towards Beachlands/Maraetai.” And again “the action of the unusual weather pattern during El Nino may have mobilised sediments within the near shore areas of the Gulf, including those originally deposited off Browns Island, and redistributed them to areas of the shore previously relatively free from sediment.” This is exactly what concerned local observers like Mrs Pat Cook Alan La Roche and Don Willans have been saying for years. Pat Cook could have told the company that for nothing! Surely a case of Pine Harbour fouling its own nest – but unfortunately everyone else’s as well. The question is how could this happen – again and again?

Vested interests, local authorities and the general public and RMA decision making

- To help answer this question I believe a recent paper published in the New Zealand Journal of Ecology – Walker et al. (2008) which examined decision making under RMA could be instructive. Walker et al.’s paper examined the question of RMA adversarial arguments around the assessment of “significance” – about the determination of what is considered significant by competing interests in our society. While “significance” in this context refers specifically to indigenous (terrestrial) habitats the principles argued are just as pertinent to marine habitats and marine taxa and indeed what constitutes “significance” in terms of adverse effects. [ix]

- Walker et al. asset that “the RMA is consistently and ‘remarkably’ evasive on just how its fundamental conflicts are to be reconciled and (following a pattern often observed in ambiguous statutes which devolves the resolution of these conflicts to local government…). The RMA provides not definition of ‘significance’. In its absence, different interests may write their different interpretations of significance, and those interpretations can and do vary considerably.”

- Walker et al. also identify the roles and influence of societal interests in the RMA process: “Determination of significance under the RMA usually involves three factions: vested interests (interests with a measurable financial stake in the outcome of a policy decision), agencies and non-vested-interest parties.” The paper goes on to define the three factions:

Vested interests – “where developers have a financial interest in gaining approval (resource consent) to exploit, destroy, or modify indigenous ecosystems and species, they and their advocates are vested interests. In the process of significance assessment, vested development interests seek development consent and the ensuing profits. Their primary interest is not protection of the environment and biological diversity, but development (Salzman & Ruhl 2000 p.675. Indeed in many cases, protection of biological diversity will stand in direct conflict with development….In advocating for narrow significance criteria, which place the burden of proof of environmental harm elsewhere, vested interests often assert their enterprise is public spirited and that their preferred outcomes add to social, economic and/or cultural well-being….Finally, they may attempt to limit participation and restrict access to the debate, e.g. by defining a high level of expertise as a requirement to participate in the debate (see Schattscheider 1960; Pralle 2006, p.51)”

And then we come to ‘Local authorities’ and while this analysis is hard hitting – and critical of the role of local government in general – I would point out one of the authors of this paper is an ARC manager.

Local authorities (district and regional councils and unitary authorities) are elected, and many expect them to act on behalf of a broad range of constituents, despite much evidence that this is the exception rather than the norm (e.g. Downs 1957; Niskanen 1971). For example, some might expect local authorities, given their statutory role to maximise a public good such as biological diversity by minimising development consents that adversely affect it. In actuality, developers and regulatory authorities often want the same thing (see Salzman & Ruhl 2000) and their interests and desires often differ from those of their electorate. The paper goes on – “The coincidence of interests between developers, elected officials, and public agency staff is so frequent and flagrant that there is a rich lexicon of common phrases (e.g. the fox guarding the henhouse) and various technical terms to describe it (co-optation and agency capture (Selznick 1949); the iron triangle (McConnell 1966; Lowi 1979); regulatory capture (Levine 1998)….Thus, without implying that this outcome is universal…there are persuasive reasons why both agencies and developers may promote narrow significance criteria even when this means environmental harm (Salzman & Ruhr 2000, p.678).

Non-vested biodiversity protection interests. “Those wishing to maintain biological diversity have little or no financial stake in the outcome. These non-vested interests would prefer criteria that are broad enough to include the full suite of features that are (or may be) important for maintaining and restoring biological diversity into the future. Because natural systems are exceptionally complex, and knowledge is incomplete, assessment of biodiversity ‘value’ (the degree of importance for maintaining biological diversity) will remain uncertain and imprecise (Myers 1993). The preference of the non-vested biodiversity interest is for significance assessment criteria that are robust to this uncertainty (‘robustly fair’ in the sense of Moilanen et al. (2008), and the probability of net environmental harm is small). Such criteria would reliably err on the side of caution, applying the precautionary principle (Raffensperger & Tickner 1999) to place the burden of uncertainty of harm in the issuing of consents on the developer. This requires thresholds for significance assessment that are inclusive and low, rather than exclusive and high.

- In summary Walker et al. declare “In New Zealand, the devolution of natural resource decision-making authority and case-by-case subjective decisions on what constitutes ‘balance’ might appear participatory and hence democratic, but are not. Devolution and case-by-case decisions will predictably intensify the dominance of vested development interests and further facilitate cumulative damage to environmental public goods [which is exactly what the Beachlands – Howick (Whitford) estuary is]including indigenous biodiversity.” Walker et al. propose that the very first questions local authorities (and therefore by inference RMA hearing commissions) should consider when making decisions around biodiversity significance criteria which involve equity and therefore politics are: (1) ‘Whose interests do these particular criteria serve?’ and (2) ‘where do these criteria place the penalty of uncertainty?”.

- In summary, bearing in mind the interesting analyses and definitions of Walker et al. the contending evidence in RMA cases between the expert witnesses for the developer on the one hand, and that of the community on the other can be a seriously unequal struggle. But in regard to the history of marine dumping in the Hauraki Gulf, again I will make the point about how often the non vested interests, members of the community – have been right. And how often the experts got it wrong. And therefore I would ask the commissioners to bear this fact in mind and take a precautionary approach when weighing up the evidence in this case ‘expert’ or otherwise.

The environmental impacts of sedimentation

- In regard to the details of the expert evidence, I propose to leave this to other submitters – I would prefer instead to deal with the wider question – which the Commission must ensure is answered to its satisfaction. That question is – given the time scales and the significant amount of material involved and the likely cumulative effects – is this activity appropriate in this particular environment; and does this activity comply with the sustainability principles and purposes of the Acts and statutory plans?

- When one reads the officer’s report and the various submissions one is struck by a glaring contradiction – on the one hand the evidence from local people about the changes in the intertidal environment from sand to mud and the progressive and relatively recent loss of species once common in the area – eg pipi and cockles; – and on the other hand evidence from the applicant’s experts that would suggest dredging and dumping (without argument unnatural activities in any natural environment) are not only not harming the environment but actually improving it! We seem to be dealing with parallel universes here. This clearly makes the task of the commissioners more challenging.

- How could this major discrepancy come about? One answer might lay in the comparative methodologies applied. From my knowledge of communities and public life, individual citizens and groups take a lot of motivating to become involved in cases like this. Clearly there is no financial incentive for community members – in fact a considerable cost both in money and in earning, leisure and family time. But the concerns of the public, all good citizens and intelligent people are too consistent to be easily dismissed. And as we see the public’s monitoring and conclusions are at considerable variance with that of the applicant’s experts.

- Another puzzle is that given the considerable ingress of both land-based sediments and sediments which have been deposited in the embayment and wider areas and sediment likely to have accumulated from previous dredging and dumping activities – notably from the Brown Island dumping; – according to the applicant’s experts the ecosystems in the embayment are in robust good health. That not only conflicts with the empirical evidence of the local community but also years of separate research by the ARC.

- Perhaps to resolve these contradictions one needs to look closely at the methodologies applied and be open to the possibility that the parties are for instance employing different sampling techniques – and such different sampling technique could conceivably produce different results. Then looking at the wider picture – first the spatial consideration, given the interaction of physical processes in the CMA and the dynamic marine environment in this area, are the control sites (which I understand are only about 1400 metres away) affected by exactly the same influences as the monitoring sites under study – which would therefore compromise their value?

- Then there is the temporal question – according to the report monitoring has only been underway for 12 years. But 12 years ago we know that the estuary was already compromised in terms of sediment because of pollution events which occurred 20 to 30 years ago – as previously outlined. So simply speaking, when the applicant’s experts make statements about the condition of the environment we need to be clear about what actually are the bases of comparison both in spatial and temporal terms.

- I would draw from the body of publicly available scientific work including the latest State of the Environment report produced by ARC scientists who are I understand are not involved with this consent – on the effects of sedimentation on the marine environment with particular reference to the Beachlands – Howick embayment (Whiford estuary). A summary of this work by Grant Barnes and Dr Jarrod Walker is attached as an appendix to my evidence.

- Whitford Embayment Studies

The ARC began monitoring land development impacts in the Mangemangeroa estuary in 2002; Turanga and Waikopua commenced in 2004. The aim of the monitoring Programme is to determine whether land disturbance activities associated with varying degrees of urbanisation in the surrounding catchments causes ecologically damaging sedimentation to the intertidal soft-sediment fauna in the estuary, and in this way to verify modelling and environmental risk predictions used to underpin development-planning decisions.

Natural estuarine environments are rich in both structural and ecological diversity and play an important role in the functioning of coastal ecosystems. There is a growing awareness and evidence that sediments pose a threat to the ecology of estuaries. Estuaries are particularly vulnerable to increased levels of sedimentation, as they act as natural retention systems. Accelerated deposition of land-derived sediment leads to habitat modification and impacts on estuarine ecology by killing, displacing, or damaging components of the macrobenthic community, resulting in changes to the abundance and distribution of benthic organisms and potentially the functioning of the system. Broad-scale degradatory habitat changes can result in stressed populations, especially adjacent to habitat transition zones. Thereafter relatively “small” changes in sedimentation rates may have ecologically significant effects.

Previous surveys and experiments conducted in the Whitford embayment demonstrate negative impacts of fine terrestrial sediments on benthic communities. The magnitude of impact depends on the depth of mud deposited (silt and clay sediment fractions), spatial extent of effect, persistence of deposits, the frequency of depositional events and the sensitivity of the impacted community. Ecological repercussions can be both short-term catastrophic and long-term chronic in nature. Potential ecological responses include both structural and functional changes to benthic communities. For example, loss of sensitive species[2], changes in biodiversity, reduced oxygenation of surficial sediment, shifting microbial activity to anaerobic processes, diminished light levels and restricted photosynthesis by microphytobenthos (microalgae), and interference with feeding processes across the sediment surface.

Events producing thinner mud layers occur more frequently than the catastrophic events described above. A study in Whitford investigating the impact of thinner mud layers on benthic communities showed that three millimetre thick layers changed the abundance of common taxa and macrobenthic community structure over 10 days and 5 mm layers reduced the abundance of common taxa by around 40% over 10 days. A cumulative affect of frequent additions of mud on macrobenthic communities was observed with the magnitude of ecological effect being larger with monthly, repeated depositions of mud, compared to a single deposition.

The regulatory status of the receiving environment

- At almost every stage of the history that I have outlined, in response to public outrage at their decisions, apologetic consenting authorities have explained to the public that “their hands were tied” by the constraints of existing legislation. After the Browns Island incident it was asserted by the ARA Regional Water Board that the Water and Soil Conservation Act would ensure a better outcome in terms of environmental protection. After the Water Board consent to allow POAL to dump off the Noises made under the Water and Soil Conservation Act 1967 it was apologetically explained that the new Resource Management Act would in future mean that such consents would be much more difficult to gain. Yet I would appear that at all times the legislation of the day did enable decision makers to protect the marine environment from dumping if they had a mind to.

- I have outlined how for during the mid 90’s the in regard to the Resource Management Act, the ARC Regional Policy Statement and the Regional Plan (Coastal) Plan were deliberately weakened by political decisions – against the overwhelming weight of public submissions. Fortunately in regard to the activities of the main players in marine dredging and disposal this has not been as damaging as it could have been. Over the last 16 years of so most of the principal parties namely Ports of Auckland and Auckland marina owners acknowledging growing environmental knowledge and awareness have accepted the weight of public opinion, complied with the DOAG agreement and have stopped dumping dredgings within the Hauraki Gulf. They have either placed dredgings within contained reclamations such as at the Fergusson container terminal or disposed of dredgings at the deep water site outside the Hauraki Gulf. All that is except Pine Harbour Marina Ltd.

- However apart from the cumulative adverse effects of Pine Harbours dumping activities on the marine ecosystems of the estuary over the past 20 years which other submitters are addressing in their evidence, there are compelling reasons why this application should be declined and why the situation is different from it was back in 1997.

- But before I do that I would refer to the Regional Plan (Coastal) gives statutory recognition to the DOAG agreement. Policy 17.4.3 states “In assessing proposals for the disposal of dredged material in the Hauraki Gulf and other parts of the Auckland coastal marine area where relevant, regard shall be had to the recommendations of the Disposal Options Advisory Group (DOAG) in terms of:

a the disposal of significant quantities of dredged material; and

b the disposal of highly contaminated dredged material ‘

I was rather surprised to read that the officer’s report to this hearing dismisses this awkward policy by claiming that while the amount of material to be dredged in this case (60,000 m³) is “significant” it is “not large” relative to that dredged by Ports of Auckland and the other marinas!

- The dumping site covers 49 ha – somewhat larger than nearby Omana Regional Park (40ha) and the channel in question dissects a CPA2 (Coastal Protection Area 2). In addition to this, the dumping area is as the report says “in close proximity” to an area of even higher sensitivity a CPA 1 (Coastal Protection Area 1). These are ARC designations applied to recognise the special sensitivity of these areas and to ensure their better protection. Overlaying these designations is an ASCV ‘Area of Special Conservation Value’ separately designated by the Minister of Conservation. The explanations for what these designations actually mean are set out in the Coastal Plan ( I have attached as an appendix) but the names are self explanatory – they are meant to be taken seriously. So I am frankly bemused that the officer’s report brushes over the important fact that this part of the coastal marine area, due to its special sensitivity and conservation value has two layers of extra protection placed over it – one from the ARC and one from DoC. Given the nature of the activities in question and the proximity to these sensitive areas, in a dynamic marine environment, clearly these areas must be impacted by the dredge dumping. One recalls that when tracer die was applied to ‘reagitated dredging’ sediments, it was revealed in full colour how suspended sediments from within the Marina quickly spread over a very wide area much further than the 49 ha dumping zone, and of course into the adjacent protected areas – as well as the beach and foreshore. Are we really confident that this doesn’t happen with the ‘thin layer’ sediments- which are actually being dumped a lot closer to the CPA 1 and ASCV than the Marina?

- In this regard I draw the commission’s attention to the Regional Plan (Coastal) which states section 17.4.1. The deposition of any waste or other matter in Coastal Protection Areas, Tangata Whenua Management Areas, or any site, building, place or area listed for preservation in Cultural Heritage Schedule 1 shall be avoided where it will result in more than minor modifications of, or damage to, or the destruction of the values contained in these places or areas.

Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act

- But the area in question has an even more enhanced status. In February 2000 Parliament enacted the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act. The Hauraki Gulf Marine Act is in three parts. The first part focuses on management of the Gulf and elevates the status and protection of the Gulf in terms of the RMA; the second part establishes the Hauraki Gulf Forum; and the third part deals with the Marine Park itself. The long preamble of the Act is a binding statement to be used as a guide to interpretation of the Act and Parliament’s purpose in enacting this law. Paragraph (6) is instructive: People use the Gulf for recreation and for the sustenance of human health, well-being, and spirit. The natural amenity of the Gulf provides a sense of belonging for many New Zealanders and for them it is an essential touchstone with nature, the natural world, and the marine environment of the natural world.

- Sections 7 and 8 of HGMP Act are legally unique. They comprise the first National Policy Statement ever issued under the Resource Management Act and the two sections also comprise a New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement. Unfortunately officer’s report makes a quick nod of the head in the direction of the HGMP Act and moves on – again as if nothing had changed from 1997.

- However the provisions of Sections 7 and 8 of the HGMP Act which did not exist in the mid 1990s and which comprise a National Policy Statement and a New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement are of critical importance to the deliberations of this case. They are therefore worth quoting in full.

- Section 7 – Recognition of national significance of Hauraki Gulf

- The interrelationship between the Hauraki Gulf, its islands, and catchments and the ability of that interrelationship to sustain the life-supporting capacity of the environment of the Hauraki Gulf and its islands are matters of national significance.

- The life-supporting capacity of the environment of the Gulf and its islands include the capacity –

- to provide for –

- the historic, traditional, cultural, and spiritual relationship of the tangata whenua of the Gulf with the Gulf and its islands; and

- the social, economic, recreational, and cultural well-being of people and communities:

- to use the resources of the Gulf by the people and communities of the Gulf for economic activities and recreation:

- to maintain the soil, air, waters, and the ecosystems of the Gulf.

86. Section 8 – Management of Hauraki Gulf

To recognise the national significance of the Hauraki Gulf, its islands and catchments, the objectives of the management of the Hauraki Gulf, its islands, and catchments are –

- the protection and, where appropriate, the enhancement of the life-supporting capacity of the environment of the Hauraki Gulf, its islands and catchments;

- the protection and, where appropriate, the enhancement of the natural, historic, and physical resources of the Hauraki Gulf, its islands and catchments:

- the protection and, where appropriate, the enhancement of those natural, historic, and physical resources (including kaimoana) of the Hauraki Gulf, its islands and catchments with which tangata whenua have an historic, traditional and spiritual relationship:

- the protection of the cultural and historic associations of people and communities in and around the Hauraki Gulf with its natural, historic and physical resources:

- the maintenance and, where appropriate, the enhancement of the contribution of the natural, historic and physical resources of the Hauraki Gulf, its islands, and catchments to the social and economic well-being of the people and communities of the Hauraki Gulf and New Zealand:

- the maintenance and, where appropriate, the enhancement of the natural, historic, and physical resources of the Hauraki Gulf, its islands and catchments, which contribute to the recreation and enjoyment of the Hauraki Gulf for the people of the Hauraki Gulf and New Zealand.

- Unfortunately the advent of the HGMP Act and the added complexity this can bring to RMA decisions has not met with universal approval from what I would call the ‘RMA sector’ which would include a number of planners, RMA lawyers, council officers and even one or two Environment Court judges.

- This has been manifested in two ways. A lack of enthusiasm by the councils in the territories covered by the Act to comply with the obligations to treat sections 7 and 8 of this Act as a New Zealand coastal policy statement and a National Policy Statement by amending their statutory plans accordingly. And of course dismissive references in some judgements. On the other hand please see examples of the HGMP significantly influencing the outcome of other judgements.[x] However regardless of what individuals think of it – the Act is law and the Law is of course the Law

- With this in mind I would draw the Commissions attention to a little noted section of the HGMP Act.

89. S.13. Obligations to have particular regard to sections 7 and 8

Except as provided in sections 9 to 12, in order to achieve the purpose of this Act, all persons exercising powers or carrying out functions for the Hauraki Gulf under any Act specified in Schedule 1 must, in addition to any other requirement specified in those Acts for the exercise of that power or the carrying out of that function, have particular regard to the provisions of sections 7 and 8 of this Act.

While as I have mentioned Part One of the Act is usually what people focus on –

Part 3 of the Act deals with the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park itself and to my knowledge has rarely if ever been referred to in any application or case involving activities in the coastal marine area of Hauraki Gulf. The Marine Park embodies inter alia the Conservation islands, marine reserves, wildlife refuges, appropriate reserves and so on. However s.33 (c) states the Park also consists of all foreshore and seabed…and interestingly s.33 (e) all seawater within the Hauraki Gulf.

In this regard I draw the Commission’s attention to s.32

90 S.32 Purposes of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park

The purposes of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park are –

to recognise and protect in perpetuity the international and national significance of the land and the natural and historic resources within the park:

- to protect in perpetuity and the for the benefit, use, and enjoyment of the people and communities of the Gulf and New Zealand, the natural and historic resources of the Park including scenery, ecological systems, or natural features that are so beautiful, unique , or scientifically important to be of national significance, for their intrinsic worth:to recognise and have particular regard to the historic, traditional, cultural, and spiritual relationship of tangata whenua with the Hauraki Gulf, its islands and coastal areas, and the natural and historic resources of the Park:to sustain the life-supporting capacity of the soil, air. water, and ecosystems of the Gulf in the Park.

- Therefore in terms of preamble of the Act, in terms of s.7 and s.8 (the legally unique National Policy Statement and New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement section) which under s.13 this commission must have “particular regard to”; and in terms of the legal purposes of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park, it would be logical to conclude that the activity of dumping dredgings in this particularly sensitive area of the Hauraki Gulf, in the face of opposition of the local community, and the tangata whenua is not only incompatible, but I submit deeply offensive to the whole purpose of the Marine Park.

- Recreational and community amenity issues

As noted in addition to greater emphasis on the need to protect environmental values of the Hauraki Gulf exemplified by the repeated phrases “protect and enhance” in sections 7 and 8, (in addition to the “avoid, remedy and mitigate” of RMA), the HGMPA is noteworthy for the emphasis placed on tangata whenua values and community recreational values. On one level it is fair to say the role of Pine Harbour Marina as an asset for recreational boating is very much in keeping with the spirit of the Act – but the dumping activities are certainly not. In the past Pine Harbour berth holders have signed form letters supporting dumping as critical to their enjoyment of recreational boating activities. No-one is challenging their rights to berth at Pine Harbour but as Policy 3.1.1 of the New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement reminds us “Use of the coast by public [eg by use of marinas] should not be allowed to have significant adverse effects on the coastal environment, amenity values, nor on the safety of the public, nor on the enjoyment of the coast by the public.”

If the adverse effects of dumping could be avoided, then Pine Harbour Marina could be considered a valuable recreational asset for the region and the Hauraki Gulf.

The cost/benefits of complying with DOAG agreement

As I have indicated earlier most of the other dredging operators comply with DOAG and dispose dredgings at the deep water site outside the Gulf or on land.

The officer’s report dedicates quite a lot of effort to examining the costs of various options of dredging and disposal and this work is quite useful.

For instance the officer’s report indicates that the additional disposal costs of disposing of the marina entrance sediment is “less than 1% of the annual operating cost “– and that “this additional cost would be even less if the cost of the likely extra monitoring of the effects of the disposal of the marina basin sediment is added.”

This would also logically apply to the costings of disposal of the approach channel dredgings.

The officer’s report identifies the approximate cost difference between the applicant’s preferred thin layer disposal method as $40m³ while deep sea disposal costs are $50m³. An overall cost difference of $20,000 -$30,000 per 3000m³

As the officer’s report points out: “if the combined volume of dredged sediment from the marina basin and approach channel, approximately 4550m³/year (rather than the amount applied for) were to be disposed of to the deep sea disposal site at a cost between $50m³ and $60m³ this would equate to an annual increase in dredging costs of between $18,000 and $36,000 or between 2% and 4% of the marina’s annual operating cost. “ However as I understand it the applicant is asking for consent to dispose of significantly less than 4550m³ .What the applicant is asking for is only 3600m³ falling to 3500m³. Therefore the cost of disposal at the DOAG deepwater site would be cheaper than the officer’s calculations.

Then there is the question of the elevated levels of background sediments that are in the embayment for reasons we have discussed, dredging and dumping would seem to be continuing to move around a lot of the same material – at a lot of financial cost for the applicant and of course different costs for the environment and the community. Deep sea or land disposal would have the extra benefit of progressively removing or reducing the sediment in the embayment. This may mean dredging has to be undertaken less frequently.