‘Navigators & Naturalists’ – the book

Next year 2019 will be the 250th anniversary of the visit to New Zealand of James Cook and the Endeavour. No doubt, any commemoration will be accompanied by controversy and debate but hopefully the anniversary will stimulate renewed interest in the Age of Discovery and its fundamental impact on our nation’s history. For some years now I have been writing a book; as it happens it’s not about Cook but about his seagoing contemporaries, most of whom were French.

Navigators & Naturalists – French exploration of New Zealand and the South Seas 1769-1824 weaves together geographic, natural and human history. It sets the scientific exploration of New Zealand and the Pacific in the context of the French Enlightenment with its veneration of science and philosophy and the quest to map the whole world – and everything in it – minerals, plants, animals and peoples, that fuelled the Age of Discovery.

It is a rather big book set out in five parts. The prologue, the scene-setter, is about Bougainville, his ‘discovery’ of Tahiti and the western mythologizing of the South Seas. Part 1, ‘To the Far Side of the World’, deals with enlightenment science, and the race between England and France to find the mythical Great Southern Continent. Part 2 ‘Jean de Surville – the Capitalist’ is about the mysterious Pacific voyage, launched from French India, at the same time as Cook’s. In fact Surville’s St Jean Baptiste and Cook’s Endeavour passed each other within hours off North Cape. It includes fascinating accounts from the journals of French navigators of first contact with Māori at Doubtless Bay. Surville’s expedition is still shrouded in enigma and controversy but is not nearly as controversial as that of Marion Dufresne.

‘The Assassination of Captain Marion Du Fresne.’ This rather fanciful depiction of the death of Marion Dufresne is by Charles Meryon (1821–1868), a naval officer stationed at the French colony of Akaroa in the 1840s. Meryon later became a celebrated artist.

‘Assassinat du captaine Marion du Fresne a la Baie des Iles, Nouvelle Zelande, 12 Juin 1772.’ Crayon, pencil & chalk on paper with linen backing 1000 x 2000 mm. G-824-3. Collection. Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand.

His visit to the Bay of Islands in 1772 is covered in Part 3, ‘Marion Dufresne – Enlightenment Martyr?’ Again there are detailed accounts of Māori-European interactions and some intriguing natural history observations. Marion’s assassination along with 24 of his men at the Bay of Islands led to a brief but vicious war between the French and Māori. For most part, the visit had been an idyllic sojourn of harmonious relations fulfilling its commander’s philosophical notions of the ‘noble savage’ but then, for reasons never satisfactorily explained, it suddenly turned terribly violent. Revisiting the reasons behind Marion’s killing, my ‘cold case’ review of the evidence comes up with an explanation different from that now widely accepted by contemporary academics and historians. Challenging received wisdom tends be controversial so the reaction will be interesting.

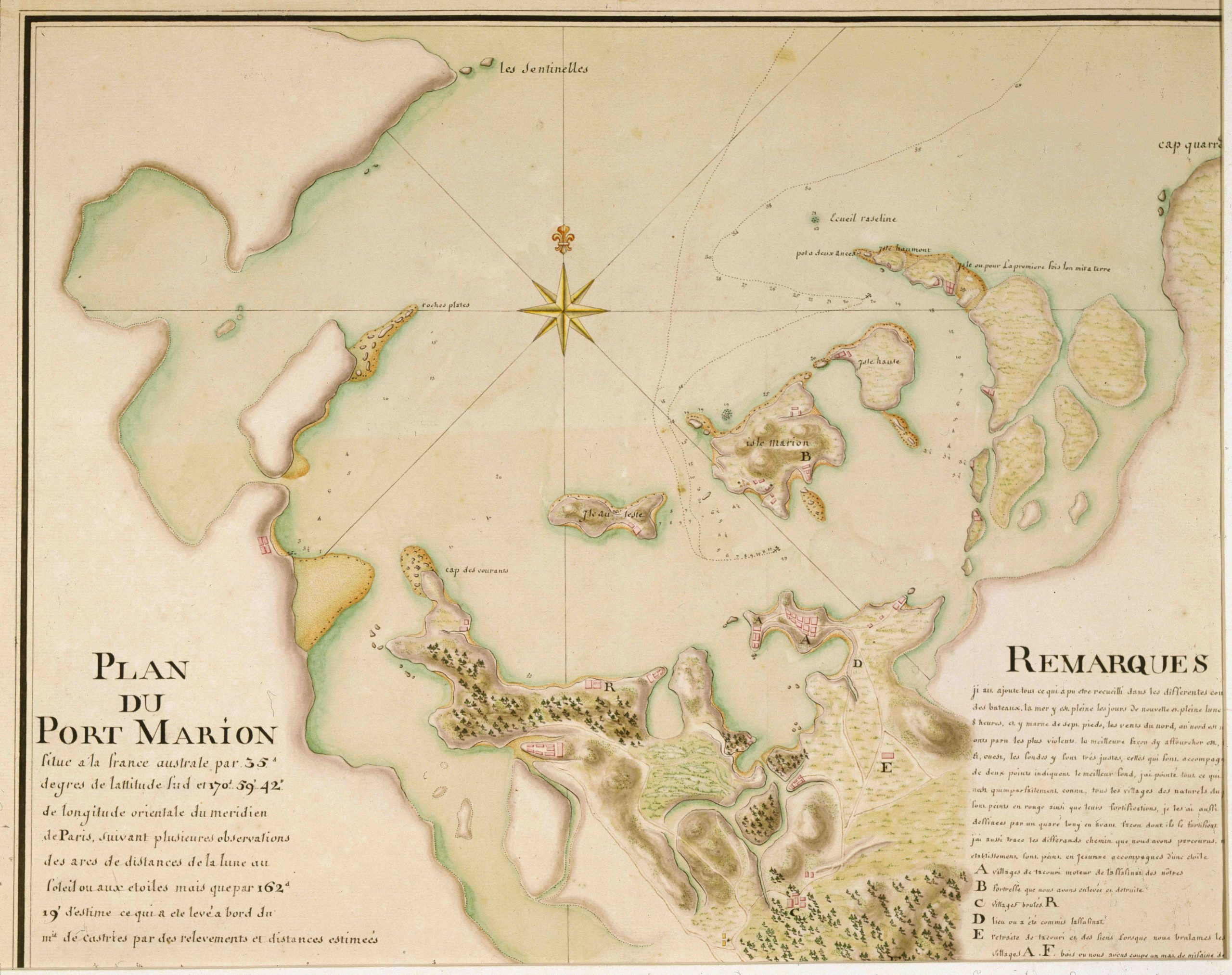

Chart of the Bay of Islands probably by Bernard Jar du Clesmeur of the Marion Dufresne expedtion 1772. Finished watercolour chart. Cartographic historian Jeremy Spencer described it as ‘perhaps the most aesthetically pleasing manuscript chart of first contact New Zealand in existence’. It was presented to the Peabody Museum,USA, by an anonymous donor in 1950. Its existence until then is unknown.

‘PLAN DU PORT MARION.’ Unsigned. Phillips Library, Peabody Museum, Salem, Massachussetts, USA. M5469. Photograph M. W. Sexton.

Part 4 deals with the expeditions of La Pérouse and d’Entrecasteaux, the French Revolution, the further development of the natural sciences during the revolutionary period and the reign of Napoléon Bonaparte.

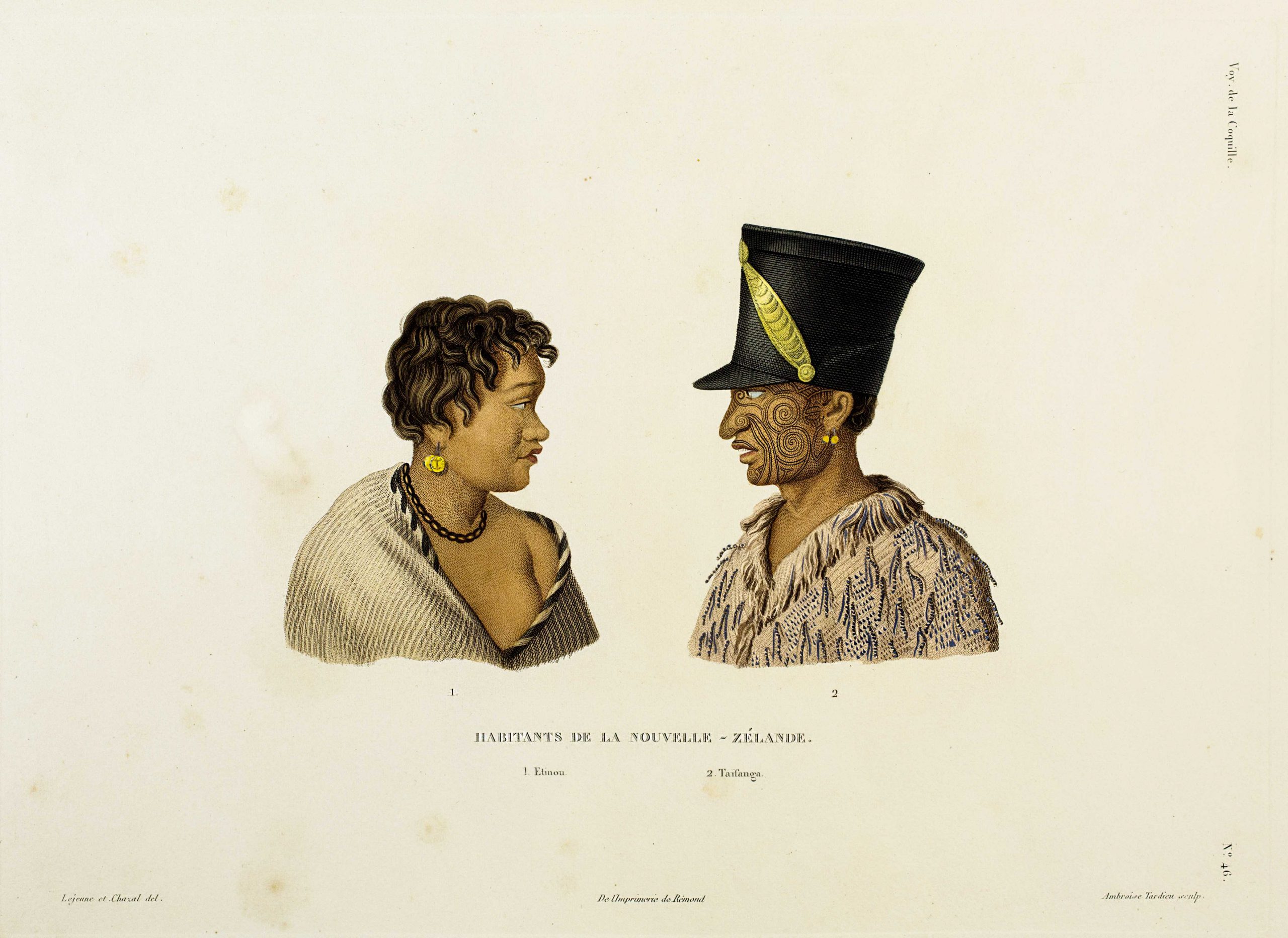

Finally, Part 5 ‘Vicit Scientiam – science victorious’ is the book’s ‘grand finale’. It covers the successful La Coquille expedition (1822-1825) of Louis-Isidore Duperrey which visited the Bay of Islands at the height of the Musket Wars. There are fascinating anecdotes about the powerful Māori rangatira, including Hongi Hika and Tui (or Tuai) and at the other of the social scale captive slaves, including the vivacious and brave Tinu, known to the sailors as ‘Nanette’.

Tinu & Taiwhanga. 1824. Strong young personalities of different social status who made an impression on the French. Tinu called by the sailors ‘Nannette’ was an enslaved captive. She impressed the French by her vivacity and by diving into the sea during a gale to rescue an old woman. Taiwhanga was the nephew of paramount chief Hongi Hika. He had travelled home from Sydney on La Coquille after staying with Samuel Marsden. Taiwhanga befriended d’Urville and later became one of the earliest Māori Christian leaders.

‘HABITANTS DE LA NOUVELLE-ZÉLANDE. 1. Etinou. 2. Taïfanga.’ Engraving by Tardieu, after Lejeune and Chazal. Plate 46. Voyage sur La Coquille. Atlas Histoire du Voyage. (1828). Auckland War Memorial Museum.

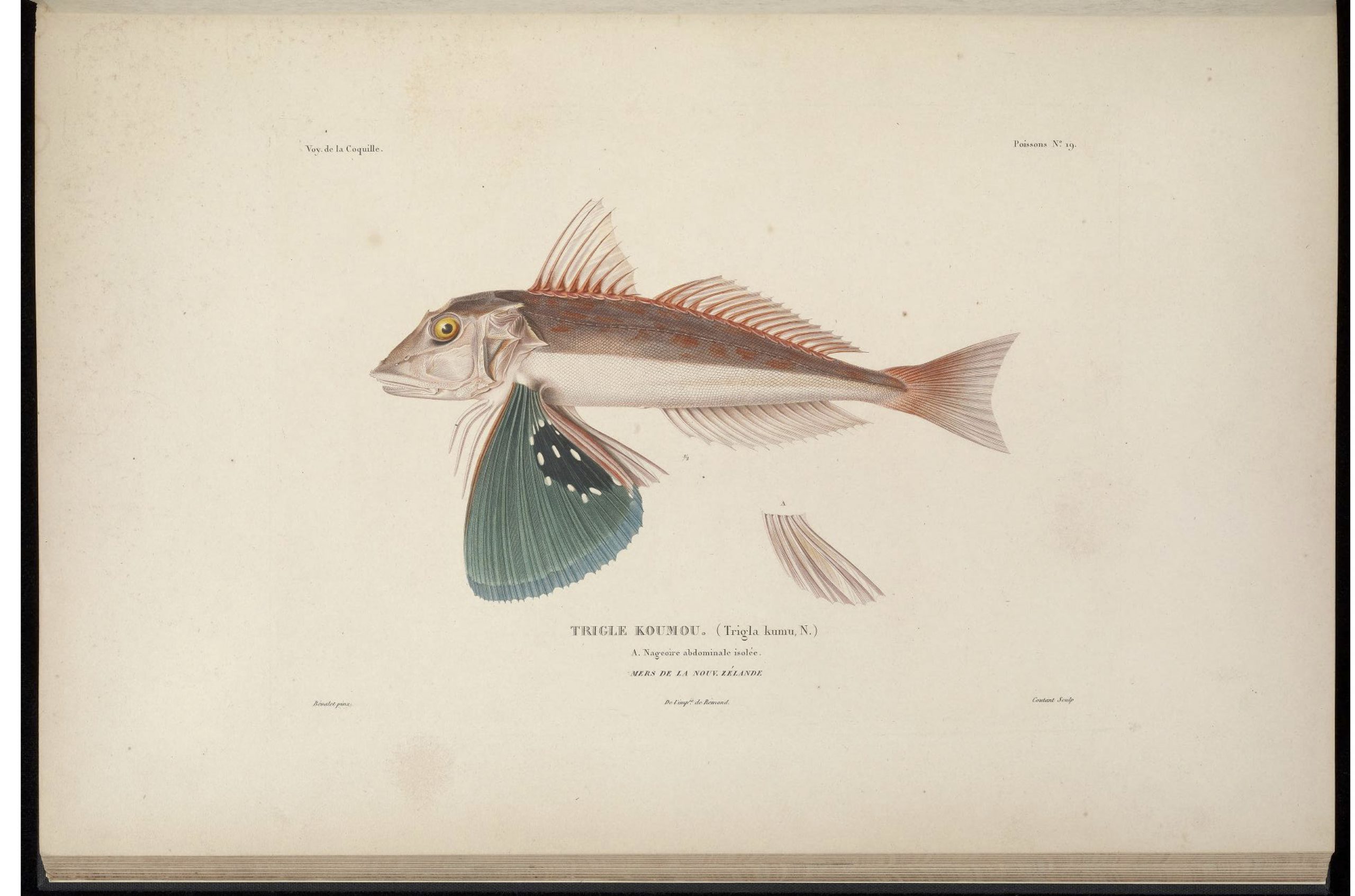

Duperrey’s scientific expedition featured the naval officers-come-naturalists René Primevère Lesson and Jules-Sébastien-César Dumont d’Urville whose pioneering work in zoology and botany has left an enduring legacy in the natural sciences of New Zealand. I think readers will be surprised at the number of native birds first described and named for science by the French and will find interesting the story of the original but unrecognised scientific name given by Lesson to the North Island brown kiwi. It was Lesson too who introduced the Māori name ‘kiwi’ to the world of ornithology. Incidentally research related to this book led to the rediscovery of what would seem to be the oldest existing specimens of the kiwi in existence. One of which, collected by d’Urville much to the astonishment of the curators of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris was found only a few months ago, ‘hidden in plain site’ on public display in the Museum’s ‘Grande Galerie de l’Evolution’.

The book also features a number of interesting supporting characters, barely remembered in their native France, let alone New Zealand. For instance Pierre Monneron who came to New Zealand with Surville and twenty years later played a key role as a radical politician in the French Revolution. Also, from the opposite side of the revolutionary divide, the 20-year-old noble, Ambroise Bernard Jar du Clesmeur, elevated to command the two-ship expedition of Marion Dufresne after his leader’s death. Young du Clesmeur produced a remarkably handsome sketch of Mt Taranaki which I discovered last year in the margin of his navigation journal in the Paris archives. It’s the oldest known artwork of the iconic maunga in existence and is now published for the first time, featured on the book’s cover. Then there is the heart-touching story of the first woman to visit New Zealand, Louise Victoire Giradin who disguised as a man was a member of d’Entrecasteaux’s crew. And from that same 1793 expedition, Raoul and Kermadec, world famous as geographic names but unknown as men. We spend some time on the back-stories of Joseph Raoul, the sailor from the lower-decks who rose to be a hydrographer, then a fighting commander, twice badly wounded in the Napoleonic Wars, and a rather different personality, much-loved by his crew, the intellectual noble Jean-Michel Huon de Kermadec. Kermadec along with many of the French Pacific explorers did his fighting in the earlier American War of Independence where he was decorated for gallantry at the siege of Savannah. He died en mission at New Caledonia a few weeks after visiting New Zealand and the archipelago named for him. As the saying goes ‘wooden ships and iron men’!

During the latter stages of the book I was fortunate to make contact with the Kermadec family who generously sent me an unpublished family history and an image of their famous ancestor, which I have used in the book. So while a few fortunate New Zealanders have visited the Kermadecs (the islands), I reckon I’m the only one to send a Christmas card to the Kermadecs (the family).

Navigators & Naturalists I hope will go some way to restoring an important chapter of our past that has been lost – the French history of New Zealand.

Navigators & Naturalists – French exploration of New Zealand and the South Seas 1769-1824. Bateman Books. Hard back. RRP $69.99 available at all good booksellers.

Also available at online outlets for cheaper prices: https://www.mightyape.co.nz/product/navigators-naturalists-hardback/27604946?gclid=Cj0KCQiAjZLhBRCAARIsAFHWpbH7WdKLSbbd74hmF9lJ2TIfUAQzIOdEZLkAhOmKs4HG2XUh1pG9WjwaAs69EALw_wcB

https://www.thenile.co.nz/books/michael-lee/navigators-naturalists/9781869539658?gclid=Cj0KCQiAjZLhBRCAARIsAFHWpbHX5W2SpFXs0cq6TRbUwqq_ep9IZYPRcHtOPStUNGy4qj0ISdszRdIaApsvEALw_wcB

I really enjoyed your book. Thanks.

My thanks to you Dan.

Well crafted. Illustrations superb.

Thanks very much Julian

Fascinating read. Gives a real ‘first hand’ experience through meticulous detail and provides great contextual insight from both European and Maori points of view. Really enjoyed the read and shed light on an area of our history I knew little of.

Thanks very much Ed.

Please accept my apologies for the delay in responding to you.

Much appreciated.

Best wishes,

Mike

Mike, I’ll have to have a read of your book, sounds interesting.

Discovered JFM de Surville whilst researching my family tree, he was the brother of my 6x great grandmother, though I’d never heard of him. His name was mentioned as an ‘exploreur de Nouvelle Zealande’ and I thought who is this guy?

As a kiwi I thought I should have heard of him, anyway there he was, large as life in the history books!

Somewhat shocked at his poor treatment of the locals in the Far North. Not good.

Cheers, Dee (Otago)

Thanks Dee,

Excuse my being so slow to reply. How fascinating I would be very interested to know more about your family tree in that respect. I have never been able to locate a portrait of Jean de Surville tho surely one must have existed. As for his treatment of the local people I cover this in some depth and hopefully with balance. Overall he was a good man but secretive and complicated, a man of his times. I hope you enjoy the book. Best wishes,

Mike